Parables and Prophecies: a Visual Epistle

Luz Art, Melrose Ave, March/April 2019

Postcards from the Edge

On view at Luz Art on Melrose is a retrospective selection of Biblical themed works by Wayne Forte spanning nearly 30 years. This exhibition offers the unique opportunity to view the shifting manner, both in hand and concept, of an artist who has approached Biblical themes with a clear sense of their central, urgent meaning for contemporary life, both personal and corporate. Throughout the selected works, as in Forte’s oeuvre in general, the human body, or its direct evocation, is the ultimate vehicle of spiritual experience and revelation. Few contemporary artists have depended on the figure in such a direct way to continue to hold so many of the meanings it has carried throughout the history of Western Art.

Emergency Liturgies

Forte’s Biblical works from the late 1980’s through the early 2000’s bear the marks of that self-consciously post-modern moment, with its penchant for appropriation and the rise of a second wave of neo-expressionism, which in Southern California was particularly accented with Pop. Forte’s large works from this timeframe take up, and take on, central art-historical works on Biblical themes. Not surprisingly, Forte leans heavily toward the Baroque, the paintings of Rembrandt and Rubens, among others, offering robust armatures against which Forte pits his highly aggressive painterly act. These works are shot through with layers of text as well–often Biblical passages or prayers which interweave with bodies and Forte’s highly improvisational material application. These works express well the complexity of a young artist trying to situate both his work and his person in relation to the tradition he has received and wants to question, trying to simultaneously erase and reinvigorate the eidetic images of the past. In Moriah (After Rembrandt) (1990), Forte explores the composition of Rembrandt’s Sacrifice of Isaac in a hot, high-key palette and discourteous mark-making; this work veers into hyperbole but lands on homage.

One can sense in these works that the stakes are high for a young man of obvious and sincere faith–this is not a vain or ironic exercise, and Forte’s work from this period ultimately dismisses the dark humor of Pop. Forte seems to want to discover in each of the old paintings their actual spiritual power, and to treat them not as displaced images, but as the altars most of them originally were.

Painting as Pedagogy

There is a shift in style, process, and subject that occurs in Forte’s Biblical paintings somewhere in the middle of the first decade of the 21st century. No longer looking back to an obvious set of art historical sources, Forte moved toward a direct narrative approach, reasserting painting’s long-standing role as teacher of Biblical story. While retaining the powerful, ponderous bodies present in most of his work (Forte never met a form he couldn’t make full and prosperous), Forte shifted to a less gestural and more textural paint application, making the images more clearly legible.

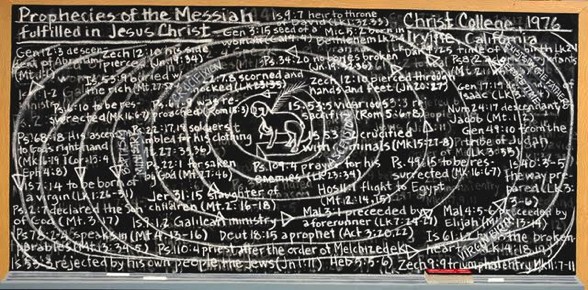

Acting as an emblem for this phase of Forte’s work is the commemorative painting Chalk Talk: Christ College (2006). Created on the occasion of the founding of a Department of Art at Concordia University, Forte presents us with a trompe l’oeil chalk board on which prophetic passages concerning the Messiah are written.

Parables emerge as frequent subjects, and they offer Forte flexible and enigmatic spaces for responding to the text. Forte treats the Parable of the Unforgiving Servant with all of the directness of Trecento fresco painting. Forte also takes up many moments from the gospels, particularly affecting is his treatment of the conversation of Jesus and the woman at the well from the Gospel of John (Forte has returned to this story on a few occasions over the years). The compression of space and large figures in the small composition of Woman at the Well (2007) express well the sudden, intimate, and taboo conversation between Jesus and a person of the wrong gender, ethnicity, and background.

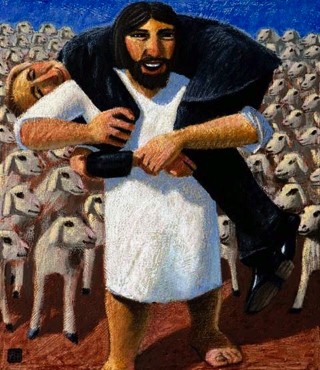

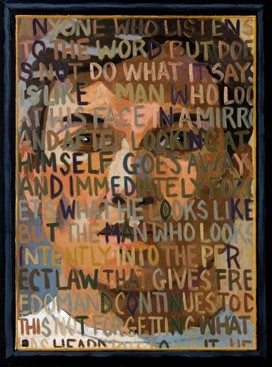

Teaching can also take the form of rebuke, and Forte intersperses his gentle parabolic images with biting critique of those inside and outside of the sheepfold. Why We believe the End Times are Near (2002), painted directly from a television tuned to a prominent televangelist network, contains vulgar figures worthy of interwar German Expressionism. Jesus’ “woes” to the Pharisees certainly come to mind here, but in Parable of the Good Shepherd (Bernie Madoff)(2010), Forte reminds us that even the worst charlatan is the object of God’s compassion. Lest we become too comfortable in our judgements of hypocrisy and deceit, Forte reminds us in A Hearer Only (2010), that without righteous action we are just the same.

Re-Contextualized Narratives

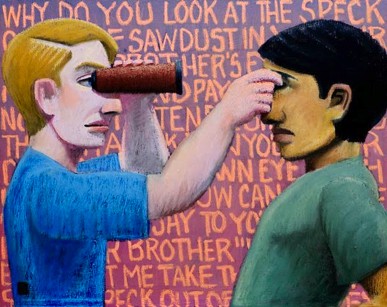

There seems to be an increasing turn, in Forte’s more recent Biblical paintings, to layer biblical stories into personal and social narratives. Born in the Philippines, and of Filipino-Irish descent, Forte is carefully attuned to the plight of the immigrant, and to the complexities of race in contemporary American society. His Brown Man’s Burden (2012), is a meditation on the metaphorical teaching of Jesus from Matthew about our perpetual propensity toward focusing on the small faults of others, while ignoring the enormity of our own. Forte’s image reads this teaching within the context of contemporary American racial dynamics. The flat space of the painting, and the clumsy movements of the figures leaves little ambiguity about the application of the sacred teaching, and echoes the tragic humor of its imagery.

Not to be missed, though it hangs, perhaps appropriately, in the bathroom at the back of Luz Art Space, is a small charcoal drawing, Holy Family Immigration (2017). Forte’s drawings have always been impactful in their directness and forceful expression of volumes, but for this work he suspends his usual powerful modeling, opting for a flatness more in keeping with his Biblical paintings. The scene presented is full of ambiguities, presenting shadowy Mary and Joseph figures against a background of dehumanizing signage, seen through a chain link fence and barbed wire. Holy Family Immigration reminds us all that the life of Jesus and his parents was not graceful like the elegant pictures in the Art History text but full of legal, religious, and social systems that sought to strip him of the very humanity he chose to take up. Forte’s raw, direct marks with the charcoal shift the meaning of the sensuous text he so often uses to contextualize his Biblical works, but where words can bring life, here they have the power to take it away. Perhaps this is the overarching message of Forte’s “visual epistle”–that the text is the path to life or to death, and so the stakes couldn’t be higher for finding new ways to visualize these sacred stories.

Review by Jonathan Puls, MFA, MA

Written during Holy Week, 2019

Wayne Forte's Website: http://www.wayneforte.com/