April 2: You Do Not Answer Me

♫ Music:

Day 29 - Wednesday, April 2

Title: You Do Not Answer Me

Scripture #1: Job 16:9–17 (NKJV)

My adversary sharpens His gaze on me. They gape at me with their mouth, they strike me reproachfully on the cheek, they gather together against me. God has delivered me to the ungodly, and turned me over to the hands of the wicked. I was at ease, but He has shattered me; He also has taken me by my neck, and shaken me to pieces; He has set me up for His target, His archers surround me. He pierces my heart and does not pity; He pours out my gall on the ground. He breaks me with wound upon wound; He runs at me like a warrior. “I have sewn sackcloth over my skin, and laid my head in the dust. My face is flushed from weeping,

and on my eyelids is the shadow of death; although no violence is in my hands, and my prayer is pure.

Scripture #2: Job 30:16–20, 26–31 (NKJV)

And now my soul is poured out because of my plight; the days of affliction take hold of me. My bones are pierced in me at night, and my gnawing pains take no rest. By great force my garment is disfigured; it binds me about as the collar of my coat. He has cast me into the mire,

And I have become like dust and ashes. I cry out to You, but You do not answer me.…When I looked for good, evil came to me; and when I waited for light, then came darkness. My heart is in turmoil and cannot rest; days of affliction confront me. I go about mourning, but not in the sun; I stand up in the assembly and cry out for help. I am a brother of jackals,

and a companion of ostriches. My skin grows black and falls from me; my bones burn with fever. My harp is turned to mourning, and my flute to the voice of those who weep.

Poetry & Poet:

“The Best Thing Anyone Ever Said About Paul Celan”

by Shane McCrae

Today you will the say the any ever

best thing any ever anyone

Said about Paul Celan

The world is if it isn’t does it matter isn’t

waiting or it might be might as well

Be if it knew and some

People for some people the wait is mostly it’s

a world in which the fact of Paul Celan

was and is always will have been and be

A fact and necessary living in such a world

is the far greater agony the wait is no

agony not compared to living in that world it is

Absurd to say he wouldn’t Paul Celan would recognize it still

No person ever is naive

but populations are naive and always will be

even innocent

is the far greater agony

It is / More like a toothache

the pain of the wait for some

More like a pain in the hole from which

You even now prepare yourself to speak

THE SILENCE OF GOD

During Christ’s earthly sojourn, he and God the Father were in continual communication. But in his most vulnerable moments on the cross, when Jesus took upon himself the full weight of humanity’s sin and God’s wrath, were unleashed in response to that sin, all communication ceased. Author Robert Nash writes, “This does not mean divinity was divided or Jesus ceased to be God, so there is some mystery in how this happened. Yet it was a clear punishment, suffered by the person Jesus in his human nature, intended for the sin of the world. This was the worst pain ever. Ever.”

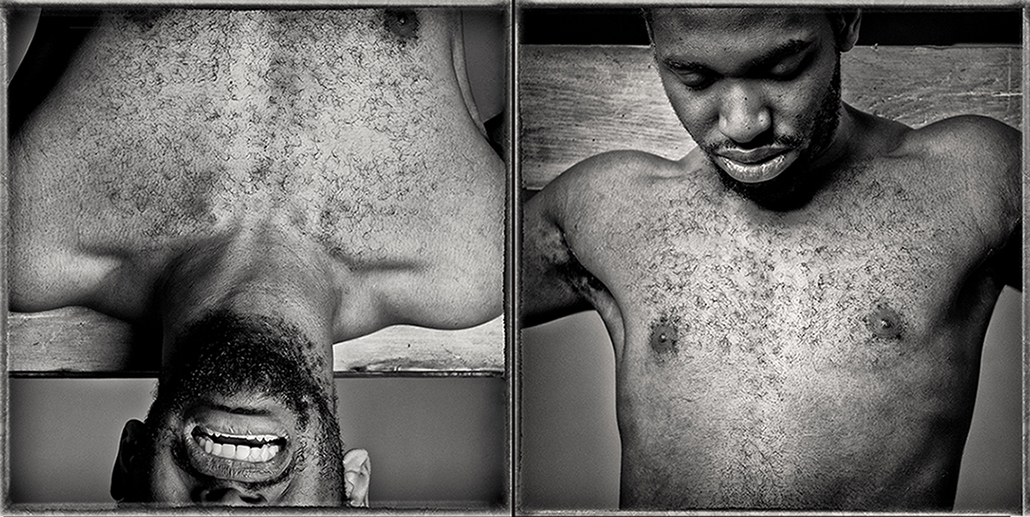

Gregory Schreck’s images from his Via Dolorosa Series trigger hazy memories of black and white photo postcards snapped at lynchings of African Americans, mostly executed in the deep South between 1877 and 1955. Over 6,000 very public hangings occurred in this era of racial segregation, egged on by hundreds of agitated, frenzied spectators. Although it’s difficult to know for sure, scholars estimate that at least one third of the victims were completely innocent of the crimes they were accused of committing. There is an uncanny similarity between the cross of Christ and the gruesome lynching tree of America’s past. I can hardly imagine the sense of utter abandonment these black men experienced as they went to their torturous deaths. “Why wasn’t God listening? Why wasn’t God watching? Why wasn’t God there?” asks Cynthia Clawson in the plaintive song, “Georgia Lee.”

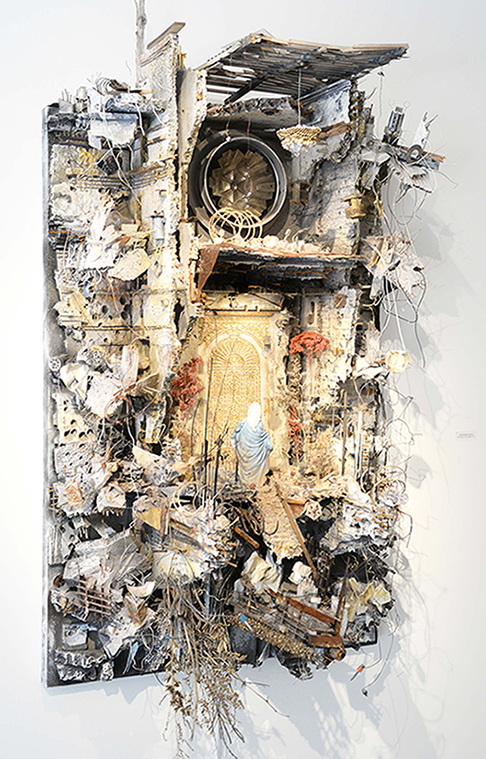

Good art sometimes asks really difficult questions. Why Have You Forsaken Us? is the disquieting title of Syrian American artist Mohamad Hafez’s striking assemblage. In it, he places a statue of Mary in front of a beautifully embellished wall that seems impenetrable, surrounded by war-torn rubble and the shell of what may have been a once vibrant civilization. Could the virtuous figure of Mary represent the devastated throngs of oppressed people beseeching God to hear their cry for help? As I contemplated this haunting artwork, I wondered how many people groups have been the subject of genocide or pestilence or horrific calamities in the course of human history? To me, Hafez’s piece deals with the destruction, desolation, and resulting suffering that takes place, often beyond our control—the sobering events of life that leave us with troubling questions concerning the nature of God. In the past decade an estimated 120 million people have been forced to flee their countries of origin. Shane McCrae’s poem (which echoes the disorienting writing style of Holocaust survivor, Paul Celan) was composed as he mulled over the absolute “horrors of our recent wars.”

Life can be brutal. No one knew this better than righteous Job, who in the pit of suffering cried, “I have become like dust and ashes. I cry out to You, but You do not answer me. . . When I looked for good, evil came to me; and when I waited for light, then came darkness” (Job 30:19-20,26). Christ could have easily recited these words as he hung on the cross. Over the ages many have clung to Job’s narrative in the midst of their own deep trials. No one knew the rampant evil in this old world more than Mother Teresa of Calcutta. Year after year, day in and day out, she and her Missionaries of Charity scooped hundreds of dying untouchables, the poorest of the poor, off the streets of Calcutta (Kolkata) and brought them indoors to die in the loving care of committed Christians who treated them with dignity and respect. Yet for the last half of her life, Mother Teresa secretly confided in her spiritual counselor that God no longer answered her or spoke to her as she hoped he would, “The silence and the emptiness is so great, that I look and do not see, listen and do not hear. . . The torture and pain, I can’t explain.” Yet even during her ongoing spiritual dryness, unable to hear God in the same ways she had in earlier years, she could still say with Job, “I know that my redeemer liveth, and that he shall stand at the latter day upon the earth” (Job 19:25).

Author Phillip Yancey has written extensively on suffering and the silence of God. He says, “We live day by day, scene by scene, as if working on a thousand-piece jigsaw puzzle with no picture on the box to guide us. Only over time does a meaningful pattern emerge.” His latest book, Where the Light Fell, is a remarkable memoir that chronicles his early life growing up in a single-family household with his older brother, Marshall. Yancey’s wounded, widowed mother, determined to keep her sons on the straight and narrow, inadvertently ended up abusing them both emotionally and spiritually. The cruelty and obsessiveness of her behavior left deep scars. Somehow Phillip was able to push through the pain, embracing and experiencing God’s redeeming grace. That was a bridge too far for his brother Marshall, whose life reeled out of control as he refused to any longer acknowledge his mother’s God. Sadly, belief often dies in those who cannot reconcile Christ’s overwhelming love for humankind with the horrendous problem of evil that to some degree they have experienced personally. We all have known suffering. We all have ached when God has not seemed to be near. But confronting the possibility of a meaningless universe head-on forces us to acknowledge God’s presence in our lives even if we don’t feel it. At the other end of the tunnel where confusion and disorientation prevail is a threshold of transformation that leads to healing and freedom. “For I am persuaded that neither death nor life, nor angels nor principalities nor powers, nor things present nor things to come, nor height nor depth, nor any other created thing, shall be able to separate us from the love of God which is in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Romans 8:38-39).

Prayer:

So here I am, Lord.

How do I talk to someone

who made the pancreas in my belly?

Who keeps my frontal lobe form disintegrating?

Do I ask you for a better world?

A thousand requests for food for the starving?

An end to wars?

How do I speak to you, Lord?

With screams and outrage?

Yes! Yes!

How else in an outrageous world?

Your Bible writers did.

They demanded answers,

Habakkuk and David,

Isaiah and Jeremiah,

they wanted to know.

Sometimes you’re so far away . . .

should I talk to you then, Lord

when I don’t feel you around?

When all my emotions say life is

A gray mist to muddle through?

Then more than ever . . .

when you’ve withdrawn your presence,

to make me grit it out alone

with a naked will.

I can still speak to the God of living flesh;

I don’t have to be a child

who lives by stomach and glands.

Lord, my days are a great jumble

of papers, hallways, soft touches and fears.

Want to hear about all that, Lord?

About the anger in my brain tonight?

The desire in my eyes this noon?

What will you tell me

when I share all I am?

—Harold Myra

Taken from the prayer “How Do I Talk To You?”

Barry Krammes. M.F.A.

Professor Emeritus, Art Department

Artist and Educator

Biola University

For more information about the artwork, music, and poetry selected for this day, we have provided resources under the “About” tab located next to the “Devotional” tab.

About the Art #1A (left):

He is Nailed to the Cross

Photograph from Via Dolorosa

Silver gelatin photograph

Photographs from Via Dolorosa

© 2025, All Rights Reserved

About the Art #1B (right):

Jesus Dies on the Cross

Photograph from Via Dolorosa

Gregory Schreck

Silver gelatin photograph

© 2025, All Rights Reserved

When asked to consider making photographs about the Stations of the Cross, fine-art photographer Greg Halvorsen Schreck and his students had just started working on a project in a rehabilitation center with refugees and torture survivors in the Chicago area. Most of the survivors were from Africa, Latin America, the Caribbean, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe. As he grew to know more about the survivors and their stories, Schreck felt he could illustrate their suffering and that of Christ using the Stations of the Cross. Consisting of a series of fourteen images portraying events in the Passion of Christ, from his condemnation by Pontius Pilate to his entombment, the series entitled The Via Dolorosa began to take shape. The name comes from the Latin phrase “Via Dolorosa,” which translates to "sorrowful road.” Schreck relates that “I didn’t expect it when we started, but the stories and the general ethos of those in our midst wounded by war, political upheaval, and unspoken violence shaped my approach to the photographs. There are those whose lives are transformed by suffering, I knew that abstractly. When I engaged collaboratively with torture survivors, many of my assumptions about photography in particular, and about art in general were turned upside down. My ongoing journey with the Cross was influenced as well.”

https://gregschreck.blogspot.com/2012/03/via-dolorosa-or-stations-of-cross.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Via_Dolorosa

https://vimeo.com/89349021

About the Artist #1:

Gregory Schreck teaches photography in the art department at Wheaton College, a Christian liberal arts college near Chicago, Illinois. He teaches both analog and digital photography, explored through artistic, documentary, and community-based approaches. In his thirty-year tenure, Schreck has also taught art history, film, video, and cinema classes. His undergraduate degree is from Rochester Institute of Technology, where he studied both commercial and fine art photography. He worked in commercial photography in New York City for ten years. Schreck completed his graduate work at New York University and the International Center of Photography in 1988.

https://www.gregschreckphotography.com/personal

About the Artwork #2:

Why Have You Forsaken Us? (multiple views)

Mohamad Hafez

2017

Mixed media, plaster, paint, rusted metal, found objects

36 x 60 x 12 in.

Artist Mohamed Hafez is an assemblage and found-object artist who works with miniatures to create sculptures that are photorealistic three-dimensional scenes that represent the urban fabric of the Middle East, and serve as his backdrops for political and social expression. In his work entitled Why Have You Forsaken Us?, a figurine of the Virgin Mary is posed atop a flight of eroded stairs. In his incorporation of Christian iconography, Hafez signals to the historically multi-faith land of Syria, transformed by the 1860 civil war in Lebanon, and 1878 expulsion policies of European governments after the “recapture” of Ottoman territory. Mary’s hands are clasped in prayer as if seeking entrance before a golden portal wrought upon the wall. The concave lines of both figure and portal at center shape the force and direction of surrounding buildings and objects, refracting outwards.

About the Artist #2:

Mohamad Hafez (b.1984) is a Syrian-American artist and architect living in the United States. His work primarily explores the stories and dislocation of Syrian history and refugees. Hafez is best known for his miniature diorama works, which depict daily life in Syria. Syrians worldwide continue to struggle to comprehend the recent aftermath of the Arab Spring and its impact on their home. As a result of Hafez’s deep personal connection to his homeland and his inability to offer meaningful assistance, this calamity introduces in him a state of homesickness, hopelessness, and helplessness. Hafez’s work is the physical embodiment of his deep feeling of immobility and being silenced that he shares with Syrians around the world. The graphic nature of his work aims to depict the atrocities being ignored globally while drawing attention to the urgent need to keep the dialogue alive. In 2021, The New Yorker produced a short film on Hafez's work, directed by Jimmy Goldblum and titled A Broken House. The film later aired on the PBS series POV during the POV Shorts installment "Where I'm From."

https://www.mohamadhafez.com/PRACTICE

https://www.mohamadhafez.com/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohamad_Hafez

About the Music: “Georgia Lee” from the album See Me, God

Lyrics:

Cold was the night and hard was the ground.

They found her in a small grove of trees.

And lonesome was the place where Georgia was found.

She's too young to be out on the street.

Why wasn't God watching?

Why wasn't God listening?

Why wasn't God there

For Georgia Lee?

Ida said she couldn't keep Georgia stayin’ out of school.

I was doing the best that I could.

Oh, but she just kept running away from this world.

These children are so hard to raise good.

Why wasn't God watching?

Why wasn't God listening?

Why wasn't God there

For Georgia Lee?

Close your eyes and count to ten.

I will go and hide but then,

Be sure to find me, I want you to find me

And we'll play all over again.

We'll play all over again.

There's a toad in the witch grass.

There's a crow in the corn.

Wild flowers on a cross by the road.

And somewhere a baby is crying for her mom.

As the hills turn from green back to gold.

And why wasn't God watching?

Why wasn't God listening?

Why wasn't God there

For Georgia Lee?

Why wasn't God watching?

Why wasn't God listening?

And why wasn't God there

For Georgia Lee?

About the Composers: Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan

Thomas Alan Waits (b. 1949) is an American musician, composer, songwriter, and actor. His lyrics often focus on society's seedy underworld and are delivered in his trademark deep, gravelly voice. He began his music career in the folk scene during the 1970s, but his music since the 1980s has reflected the influence of such diverse genres as rock, delta blues, opera, vaudeville, cabaret, funk, hip-hop, and experimental techniques verging on industrial music. A sensitive and sympathetic chronicler of the downtrodden, Mr. Waits creates three-dimensional characters who, even in their confusion and despair, are capable of insight and startling points of view. Waits has influenced many artists and gained an international cult following. His songs have been covered by such artists as Bruce Springsteen, Tori Amos, Rod Stewart, and the Ramones, and he has written songs for Johnny Cash and Norah Jones, among others. In 2011, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

http://www.tomwaits.com/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tom_Waits

Kathleen Patricia Brennan (b. 1955) is an Irish-American musician, songwriter, record producer, and artist. She is known for her work as a co-writer, producer, and influence on the work of her husband Tom Waits. Brennan and Tom Waits first met in 1978 on the set of Paradise Alley, where Brennan was a scriptwriter and Waits was making his acting debut. They met again during production of the Francis Ford Coppola film One from the Heart. Brennan is generally regarded as the catalyst for Waits' shift towards more experimental sound, beginning with the 1983 album Swordfishtrombones. Her first co-writing credit appears on Rain Dogs in 1985 for "Hang Down Your Head," and by 1992 she was his main producer and song-writing partner. Her work includes co-writing and collaborating on the albums Franks Wild Years (1987), Alice (2002), and Blood Money (2002), as well as the musicals The Black Rider (1989) and Woyzeck (2000).

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kathleen_Brennan

About the Performer:

Cynthia Clawson (b. 1948), referred to as the “singer’s singer” and called "the most awesome voice in gospel music" by Billboard Magazine, has received a Grammy and five Dove awards for her work as a songwriter, vocal artist, and musician. Her career has spanned over four decades, with twenty-two albums released since 1974. Clawson has performed in many prestigious venues and with preeminent groups, and her work has been featured in a number of films, including A Trip To Bountiful. Clawson currently resides in Houston, Texas, and is married to lyricist, poet, and playwright Ragan Courtney.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cynthia_Clawson

https://www.cynthiaclawson.com/

About the Poetry and Poet:

Shane McCrae (b 1975) is an American poet. McCrae was the recipient of a 2011 Whiting Award, and in 2012, his poetry collection Mule was a finalist for the Kate Tufts Discovery Award and a PEN Center USA Literary Award. In 2013, McCrae received a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). His poems have appeared in numerous journals and anthologies, including Best American Poetry 2010, American Poetry Review, African American Review, Fence, and AGNI. He is the author of the poetry collections Mule (2011), Blood (2013), Forgiveness Forgiveness (2014), The Animal Too Big to Kill (2015), and In the Language of My Captor (2017). McCrae was an assistant professor in the creative writing program at Oberlin College from 2015 to 2017 and is currently an assistant professor in the creative writing M.F.A. program at Columbia University.

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/shane-mccrae

About the Devotion Writer:

Barry Krammes, M.F.A.

Professor Emeritus, Art Department

Artist and Educator

Biola University

Artist and educator Barry Krammes (b. 1951) received his B.F.A. in printmaking and drawing from the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire and his M.F.A. in two-dimensional studies from University of Wisconsin, Madison. For thirty-five years, he was employed at Biola University in La Mirada, California, where he was the Art Chair for fifteen years. Krammes is an assemblage artist whose work has been featured in both solo and group exhibitions, regionally and nationally. His work can be found in various private collections throughout the United States and Canada. He has taught assemblage seminars at Image Journal’s annual Glen Summer Workshop in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Krammes has served as the Visual Arts Coordinator for the C. S. Lewis Summer Institute in Cambridge, England, and was the Program Coordinator for both Biola University’s annual arts symposium and the Center for Christianity, Culture, and the Arts for several years. Krammes was the originator of the CCCA Advent and Lent Projects.