March 31: Why?

♫ Music:

Day 27 - Monday, March 31

Title: Why?

Scripture: Matthew 27:45–53 (NKJV)

Now from the sixth hour until the ninth hour there was darkness over all the land. And about the ninth hour Jesus cried out with a loud voice, saying, “Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani?” that is, “My God, My God, why have You forsaken Me?” Some of those who stood there, when they heard that, said, “This Man is calling for Elijah!” Immediately one of them ran and took a sponge, filled it with sour wine and put it on a reed, and offered it to Him to drink. The rest said, “Let Him alone; let us see if Elijah will come to save Him.” And Jesus cried out again with a loud voice, and yielded up His spirit. Then, behold, the veil of the temple was torn in two from top to bottom; and the earth quaked, and the rocks were split, and the graves were opened; and many bodies of the saints who had fallen asleep were raised; and coming out of the graves after His resurrection, they went into the holy city and appeared to many.

Poetry & Poet:

“The Task”

by Edward Hirsch

You never expected

to spend so many hours

staring down an empty sheet

of lined paper

in the harsh inner light

of an all-night diner,

ruining your heart

over mug after mug

of bitter coffee

and reading Meister Eckhart

or Saint John of the Cross

or some other mystic

of nothingness

in a brightly colored booth

next to a window

looking out

at a deserted off-ramp

or unfinished bridge

or garishly lit parking lot

backing up

on Detroit or Houston

or some other city

forsaken at three a.m.

with loners

and insomniacs

facing the darkness

of an interminable night

that stretched into months

and years.

WHY?

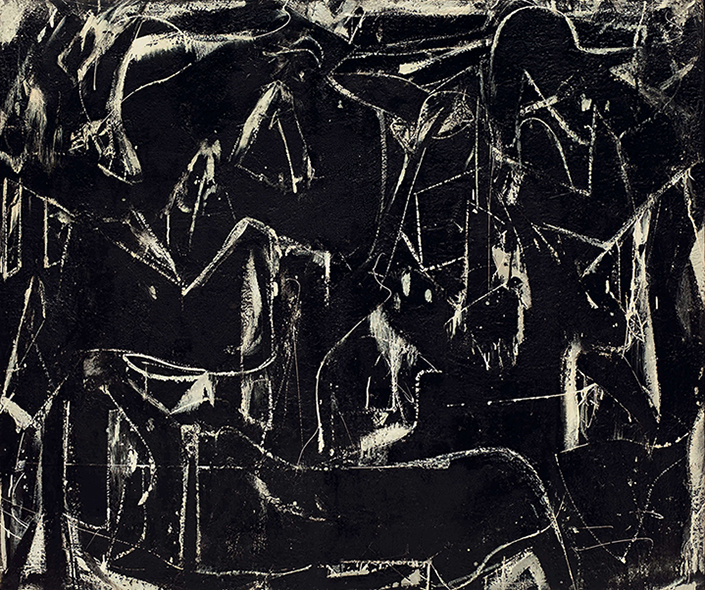

Meditating on this passage from Matthew’s Gospel is a lot like staring at de Kooning’s Dark Pond. There appears to be some way to make sense of what we see, but there’s also too much chaos to really get our heads around it.

In 1948-49, de Kooning made a series of four dark paintings that all had stark black backgrounds playing host to a jumble of undulating lines of white paint. Even though they appear quite simple in composition, the artist embedded some cryptic subtleties within them. The eye cannot help but trace the varying width, velocity, and opacity of his white lines for some explanation to their movement or shape, but none emerges. While critics can find some identifiable shapes in the other works from the series, Dark Pond remains the most mysteriously stoic of the set. Instead of meaning, the abyss stares back.

And yet, the darkened skies around Calvary surely have a double meaning. Naturally, like Haydn’s somber composition, the darkness covering the land attests to the misery and looming grief of the moment. The strange disturbances (quaking ground, splitting rocks, and disturbed graves) also speak to the inconceivable nature of his suffering. Still, however, the symbol of darkness in the biblical imagination is both one of unapproachable mystery and profound presence. So, this metaphysical thinness around Jesus’ last moments bids us to edge closer.

The mystery seems impenetrable, because we have no access to Jesus’ thoughts or feelings besides his screams and the sparse, desperate words they carry. Perhaps, under such excruciating strains, Jesus cannot verbalize his experience beyond the reflex of claiming Psalm 22’s words as his own: “forsaken.”

Trying to discern exactly what Jesus experiences here, especially in this moment of acutest pain, is certainly impossible for us. Our feeble approximations may not get closer than how Edward Hirsch concludes his poem: “facing the darkness/ of an interminable night/ that stretched into months/ and years.” The sting of utter meaninglessness seems paralyzingly close for him. “Why?” feels like a swirling black hole of doubt and crippling uncertainty, and Jesus did not spare himself from it.

While we may never fully measure the depths of his agony, we must avoid the responses of those present. Either in desperation to end his sufferings or ignorant enjoyment of the tragedy, these remind us how much humanity wants to look away from his sacrifice. As C.S. Lewis explained of Christ’s temptations in Mere Christianity, humans don’t have the fortitude to even consider how much Jesus could actually suffer. We cannot comprehend it. Only the Son of God could face this end.

So, the only proper response is to marvel at his incredible power to love. And never doubt that Christ has power over any kind of seemingly meaningless suffering we’re facing because he has already endured the worst forsakenness for us. In love, he has ensured that we will never suffer alone.

Prayer:

Heavenly Father, give us eyes to see and minds to comprehend more fully the depth of love Christ poured out for us on his cross. Bind us to Jesus, so that we might honor his life, death, and resurrection by following him more closely. Give us grace to quiet our fears and question our doubts when we face trials of our own. Let us instead find a deeper joy through fellowship with his sufferings. We ask it in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Spirit.

Amen.

Dr. Taylor Worley

Visiting Associate Professor of Art History

Wheaton College

Wheaton, Illinois

For more information about the artwork, music, and poetry selected for this day, we have provided resources under the “About” tab located next to the “Devotional” tab.

About the Art:

Dark Pond

Willem de Kooning

1948

Enamel on composition board

46 3/4 x 55 3/4 in.

Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation

Los Angeles, California

Photograph: Brian Forrest

Willem de Kooning’s move to abstraction during the late 1940s was dominated by the so-called “Black Paintings.” These pieces allowed him to test the extremes of abstraction, and develop an artistic vocabulary that enabled the fusion of natural and figurative references using the same mark making. His work like Dark Pond retains a figurative element evoking hidden anatomical and natural forms that seem to be in the midst of a struggle. The restricted palette of black and white allowed de Kooning to experiment with a loose, Cubist-style abstraction, but remnants of the human figures remain visible underneath the swirls of paint.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/483878

About the Artist:

Willem de Kooning (1904–1997) was a Dutch-American Abstract Expressionist artist. Born in Rotterdam, in the Netherlands, he moved to the United States in 1926, becoming a US citizen in 1962. In 1943, he married painter Elaine Fried. In the years after World War II, De Kooning painted in a style that came to be referred to as Abstract Expressionism or "action painting," and was part of a group of artists that came to be known as the New York School. Other painters in this group included Jackson Pollock, Elaine de Kooning, Lee Krasner, Franz Kline, Arshile Gorky, Mark Rothko, Hans Hofmann, Adolph Gottlieb, Robert Motherwell, Clyfford Still, and Richard Pousette-Dart. De Kooning's retrospective held at MoMA in 2011–2012 made him one of the best-known artists of the twentieth century.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Willem_de_Kooning

About the Music: “My God, My God Why Have You Forsaken Me” from The Seven Last Words of Christ

Lyrics:

Eli, Eli, Lama Sabactani?

Oh, My God, look upon me;

why have you forsaken me?

Why?

Oh, My God, look upon me;

why have you forsaken me?

Go not from me.

Why art thou so far from my health,

and from the words of my complaint?

Go not from me.

All they that see me,

laugh me to scorn.

Hide not thou thy face from me.

Thou hast been my succor.

Leave me not.

Forsake me not.

Hide not thou thy face, O God.

Turn thee unto me, for I am desolate

and in misery.

Oh, My God, look upon me;

why have you forsaken me?

Why?

Look upon me;

Go not from me.

My hope has been in thee,

O Lord.

Lord, in thee have I trusted.

I have said, thou art my God.

“The Seven Last Words of Our Saviour on the Cross” is an orchestral work by Joseph Haydn, commissioned in 1786 for the Good Friday service at the Oratorio de la Santa Cueva (Holy Cave Oratory) in Cádiz, Spain. It was published in 1787 and performed in Paris, Berlin, and Vienna; then the composer adapted it in 1787 for string quartet and in 1796 as an oratorio. The seven main meditative sections—labeled "sonatas"—are framed by a slow introduction and a fast "earthquake" conclusion. The priest who commissioned the work, Don José Sáenz de Santa María, paid Haydn in a most unusual way—sending the composer a cake that Haydn discovered was filled with gold coins.

About the Composer:

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732–1809) was an Austrian composer of the classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music, and his contributions to musical form have earned him the epithets "Father of the Symphony" and "Father of the String Quartet." Haydn spent much of his career as a court musician for the wealthy Hungarian Esterházy family at their remote estate. Until the later part of his life, this isolated him from other composers and trends in music so that he was, as he put it, "forced to become original.” Yet his music circulated widely, and for much of his career he was the most celebrated composer in Europe. He was a friend and mentor of Mozart, a teacher of Beethoven, and the older brother of composer Michael Haydn.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Haydn

About the Performers: The Chanticleer Singers South Africa and Odeion String Quartet

The Chanticleer Singers was formed in 1980 by Richard Cock and is regarded as South Africa’s leading chamber choir. Over the years their reputation and renown have grown as they have become known through radio and television broadcasts as well as public performances. Though based in Johannesburg, the Choir has appeared at other venues throughout South Africa, including the Grahamstown National Festival of the Arts, the Cape Town International Organ Festival, the Knysna Nederberg Arts Festival, the Sowetan’s “Nation Building” Massed Choir Festival, Durban, Pietermaritzburg, Bloemfontein, Kimberley, Pietersburg, Upington and many smaller towns, as well as in Botswana, Swaziland the United Kingdom, Namibia, the USA and Israel. Their tour of the UK was the subject of an hour-long TV-documentary, “Lands End and Beyond."

https://www.chanticleer.co.za/...

The founding of the Odeion String Quartet in 1991 can be traced back to the establishment of the Free State String Quartet at the UFS in 1960, thirty years earlier. The first members of the Free State String Quartet were Jack de Wet (first violin and leader), Noël Travers (second violin), Francois Bougenon (viola) and Harry Cremers (cello). Travers later left and was followed up by Jonas Pieters. The founding of the quartet was the beginning of string and symphony orchestra development in the Free State. The Free State String Quartet dissolved when Jack de Wet moved to Port Elizabeth at the end of 1972. The UFS piano quartet was established in the early eighties with Johan Potgieter as pianist and the three string players, Derek Ochse, John Wille and Michael Haller. The 50 year anniversary of string quartet music in the Free State and the quartet’s inheritance was celebrated in August 2010 with a special Odeion String Quartet concert where Jack de Wet was present.

https://www.ufs.ac.za/humaniti...

About the Poetry and Poet:

Edward M. Hirsch (b. 1950) is an American poet and critic who wrote a national bestseller about reading poetry entitled How to Read A Poem: And Fall in Love with Poetry. He has published nine books of poems, including The Living Fire: New and Selected Poems (2010), which brings together thirty-five years of work, and Gabriel: A Poem (2014), a book-length elegy for his son that The New Yorker called "a masterpiece of sorrow." Hirsch has built a reputation as an attentive and elegant writer and reader of poetry. Over the course of many collections of poetry and criticism, and the long-running “Poet’s Choice” column in the Washington Post, Hirsch has transformed the quotidian into poetry in his own work, as well as demonstrated his adeptness at explicating the nuances and shades of feeling, tradition, and craft at work in the poetry of others.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edward_Hirsch

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/edward-hirsch

About the Devotion Writer:

Dr. Taylor Worley

Visiting Associate Professor of Art History

Wheaton College

Wheaton, Illinois

Taylor Worley is visiting associate professor of art history at Wheaton College and director of a research project on conceptual art and contemplation. He completed a Ph.D. in the areas of contemporary art and theological aesthetics in the Institute for Theology, Imagination, and the Arts at the University of St. Andrews and is the author of Memento Mori in Contemporary Art: Theologies of Lament and Hope (Routledge, 2020). Taylor is married to Anna, and they have four children: Elizabeth, Quinn, Graham, and Lillian.