March 7: We Are Nothing Without God

♫ Music:

Thursday, March 7

We Are Nothing Without God

Scripture: Psalm 8: 3-6

When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars, which you have set in place, what is man that you are mindful of him, and the son of man that you care for him? Yet you have made him a little lower than the heavenly beings and crowned him with glory and honor. You have given him dominion over the works of your hands; you have put all things under his feet.

Poetry:

Ode to the Tiniest Dessert Spoon in All Creation

by Karen An-hwei Lee

In a new translator’s version of Genesis, there’s no Adam.

No serpent. In paradise, I don’t bleed. Fig leaf-free girl,

dear God, I say as we converse fluently without tongues,

joined as two spice-drenched beloveds in a song of songs,

could we please ask the gardener to plant a pomegranate grove

by a stand of non-fruiting olive cultivars, which don’t bloom

and aren’t so messy? Honey, I am the gardener, says God,

whose anthropomorphic footfalls caress the afternoon cool.

Wolves in our botanical garden ask nothing of any human,

eyes the hue of clementines plucked green off a young tree,

one of five in my orchard, per telltale ringless left finger:

fig, clementine, kumquat, oroblanco, and lemon. If I reside

in paradise, then I get to eat all the fruit I want, all day long.

No problem, says God, who calls me a little pouch of myrrh.

An eagle locks eyes with mine. A dove by the pool adores

the wolves as she coos, gold-amber, one stone’s throw away.

Each one carries a scent: snowy owls of shuttered skies, elk,

bobcats, melanin-rich skin of a feckless human. In paradise,

wolves and doves coexist. Once, a clementine sat forgotten

in my purse until it acquired the spots of a leopard. A world

in a lion’s eye is kohl-lined gold. Aloes and sage carve a path

through a brushy stand of Joshua trees, one which God made

after lightning struck the agave and scrub oak. Joshua trees

are chuppah arches double-wreathed with burrs, scales, fur.

Joshuas aren’t guys, so yucca moths activate their ovaries.

Wolves do not question why a male is missing in paradise.

Yes, yucca moths take care of it. Coyotes do not question

the human. Why I’m not married, why childless, howling,

and whether we’ve reached the century when God invents

a gossamer mousse garnished with absinthe-laced cherries

served in hand-fired ceramic espresso cups, a dessert to taste

together for the first time after we invent a miniature spoon

no larger than a bee hummingbird, tiniest in all creation.

WE ARE NOTHING WITHOUT GOD

At the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles there is a massive 3,040 square foot wall featuring a 2.46 gigapixel image of one section of the galaxy, as photographed by the Samuel Oschin Telescope. It’s called “The Big Picture.” Its image (which covers only 30 square degrees of deep space) shows 1.5 million stars. Ordinarily, when I visit the observatory I find this vision beautiful and inspiring. I think of God and the goodness of the creation he has made. But once, while staring at The Big Picture, something happened to me. Dwarfed by the image stretching several stories above me and away from me in each direction, I zeroed in on a single star, no more than a centimeter wide in the massive photograph. And it dawned on me that the star I was looking at was several times bigger than the sun. Suddenly, for a single moment, I felt what Blaise Pascal described: “When I consider the short duration of my life, swallowed up in an eternity before and after, the little space I fill engulfed in the infinite immensity of spaces whereof I know nothing, and which know nothing of me, I am terrified. The eternal silence of these infinite spaces frightens me.”

It’s all too easy for us to underestimate our smallness in the universe. We spend most of our lives surrounded with objects scaled to the adult human frame, and so we come to believe that this universe is also scaled to suit us. The simple fact is that it’s not. In fact, the universe is so immense that even the idea of its size is beyond our capacity. And it’s this fact that makes many who study its immensity balk at the claims of human religions. How foolish that anyone would dare to suggest that the God who made all that would even spare a thought for our planet, much less listen to the paltry concerns of one of its even smaller and less significant inhabitants. They ask, “What is man, that a God would be mindful of him?”

And in this season of Lent, I think we ought to start there—by meditating on the absurdity of God’s care. I so often think myself big. To comprehend God’s love for me I must remind myself daily that I am small. Ludicrously so. My life is unbelievably brief. My concerns and troubles are not worth mentioning even compared to other creatures who are as tiny as I am. And yet the God who spoke a billion stars into being loves me. Listens to me. Was willing to die for me.

It’s not an easy thing to think about. Nothing I can say can make you feel the way I did looking at that photograph. And it’s deeply unflattering to our sense of self to even attempt this imaginative work. But it is only in the light of our profound smallness that we can really appreciate the wonder of the psalmist and of Karen An-hwei Lee at the intimacy of God’s love and care. It doesn’t make sense. It is utterly undeserved. And remembering that this is so strips us of our sense that we are owed God’s attention, that his constant reception is only to be expected. No, Christ’s regard for me is pure, astonishing gift, for I am dust.

Prayer:

Almighty God, you have created us out of the dust of the earth: Grant that the ashes we receive in Lent may be to us a sign of our mortality and penitence, that we may remember that it is only by your gracious gift that we are given everlasting life; through Jesus Christ our Savior.

Amen.

(From the Anglican Book of Common Prayer)

Dr. Janelle Aijian

Assistant Professor

Torrey Honors Institute

Biola University

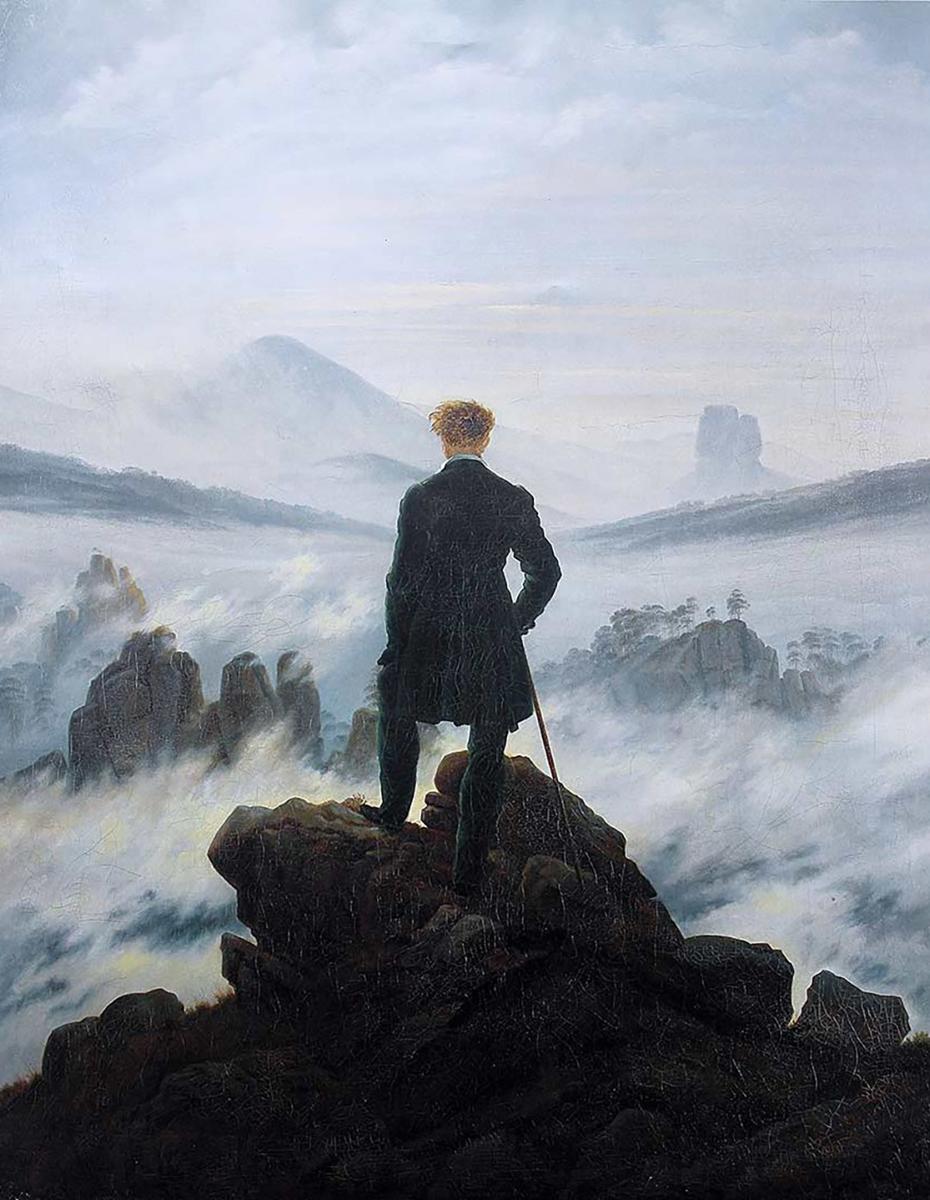

About the Artwork:

Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, 1818

Caspar David Friedrich

Oil on canvas

94.8 × 74.8 cm

Kunsthalle Hamburg, Germany

This painting depicts a formally dressed man standing on an outcropping of rocks looking out at an inhospitable expanse. In the background is a sky filled with white puffy clouds and the outline of mountaintops barely visible through the mist. As the lone figure contemplates the vastness before him, the sublimity of nature is demonstrated not in a calm, serene view, but in the sheer power of natural forces. Some have asserted that the painting suggests both man’s mastery over the landscape and the insignificance of the individual within it. Artist Caspar Friedrich is known to have made political statements in his paintings, often coded in subtle ways. Student protesters during Germany's Wars of Liberation, at the time this painting was made, wore similar clothing to what the figure is wearing. By the time this painting was completed, Germany’s new ruling government forbade this type of clothing. By deliberately depicting the figure in this outfit, Friedrich made a visual, albeit understated, stand against the government.

About the Artist:

Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840) was a German Romantic artist born in Greifswald, Swedish Pomerania (now Northeastern Germany). Before he was 20 years old, his mother, two sisters, and a brother had all died. He was known, even then, for his melancholic and ironic personality; a seriousness that was reflected in his paintings. He began studying art at the University of Greifswald in 1790 and then continued his education at the Academy of Copenhagen. He is best known for his mid-period allegorical landscapes that typically feature contemplative figures silhouetted against night skies, morning mists, barren trees or Gothic or megalithic ruins. His primary interest as an artist was the contemplation of nature, and his often symbolic and anti-classical work sought to convey a subjective, emotional response to the natural world. The artist’s legacy unfortunately suffered greatly when Hitler and the Nazis claimed Friedrich as their ideological forebear in the 1930s. They connected his rapture for the German landscape with their slogan of “Blood & Soil,” which similarly romanticized national territory and nature. It would take more than three decades, into the 1980s, before his work would be viewed and appreciated once again without the taint of Nazism.

About the Music:

“A Pile of Dust” from the album Orphee

About the Composer:

Jóhann Gunnar Jóhannsson (1969 – 2018) was an Icelandic composer who wrote music for a wide array of media including theatre, dance, television and films. His work is marked by its blending of traditional orchestration with contemporary electronic elements. In 2016, Jóhannsson signed with Deutsche Grammophon, through which he released his last solo album, Orphée. Jóhannsson was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Original Score for both The Theory of Everything and Sicario and won a Golden Globe for Best Original Score for the former. His scores for Mary Magdalene and Mandy were released posthumously.

About the Performers:

Air Lyndhurst String Orchestra is named after a historic Methodist Church in the Lyndhurst area of London. It is now the headquarters of AIR Studios, the top-flight independent recording facility created by Sir George Martin, the famed record producer, who is often called the "Fifth Beatle" for his part in creating the historic rock group's innovative recorded sound. AIR Studios has several recording halls, including the original church sanctuary, which is excellent for symphonic film soundtrack scoring. Such scoring usually uses a group of professional freelance musicians hired for a given job by an orchestral contractor. Each job uses the best available musicians from London's enviable pool of top-rank musicians, many of whom are members of the city's five international-quality, permanent symphony orchestras.

Anthony Weeden has established an outstanding career as an orchestral conductor and orchestrator with a keen desire to step beyond traditional musical boundaries. He is frequently in demand by orchestras and ensembles around the world because of his vast repertoire, ability to work in diverse musical styles and genres, and friendly character make him frequently in demand with orchestras and ensembles around the world.

About the Poet:

Karen An-hwei Lee (b. 1973) is a Chinese American poet, translator, and critic. She earned an MFA in creative writing from Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, and a PhD in literature from the University of California, Berkeley. Lee has received six Pushcart Prize nominations, the Poetry Society of America's Norma Farber First Book Award, the Kathryn A. Morton Prize for Poetry from Sarabande Books, and the July Open Award sponsored by Tupelo Press. Lee’s work appears in journals such as The American Poet, Poetry, Kenyon Review, Gulf Coast, Journal of Feminist Studies & Religion, Iowa Review, and IMAGE: Art, Faith, & Mystery. The recipient of an NEA Fellowship, Lee currently serves as a Professor of English at Vanguard University of Southern California in Costa Mesa, California.

About the Devotional Writer:

Dr. Janelle Aijian

Assistant Professor

Torrey Honors Institute

Biola University

Janelle Aijian is an Associate Professor of Philosophy teaching in the Torrey Honors Institute at Biola University. She studies religious epistemology and early Christian ethics, and lives with her husband and their two children in La Mirada, CA.