April 15: Behold the Human Being — Behold a Righteous Man

♫ Music:

Monday, April 15

Behold the Human Being--Behold a Righteous Man

Scriptures: John 19:5, Matthew 27:11-14, 18-19, 22-25

So Jesus came out wearing the crown of thorns and the purple robe. Pilate said to them, “Behold the man!” Now Jesus stood before the governor, and the governor asked him, “Are you the King of the Jews?” Jesus said, “You have said so.” But when he was accused by the chief priests and elders, he gave no answer. Then Pilate said to him, “Do you not hear how many things they testify against you?” But he gave him no answer, not even to a single charge, so that the governor was greatly amazed. For he knew that it was out of envy that they had delivered him up. Besides, while he was sitting on the judgment seat, his wife sent word to him, “Have nothing to do with that righteous man, for I have suffered much because of him today in a dream.” Then Pilate said to them, “What shall I do with Jesus who is called Christ?” They all said, “Let him be crucified!” And he said, “Why? What evil has he done?” But they shouted all the more, “Let him be crucified!” So when Pilate saw that he was gaining nothing, but rather that a riot was beginning, he took water and washed his hands before the crowd, saying, “I am innocent of this man's blood; see to it yourselves.” And all the people answered, “His blood be on us and on our children!”

Poetry:

From “Holy Week: Illuminations”

by Lisa Russ Spaar

Monday

Dove-gray, cursive basket of the dogwood,

a nuthatch alighting in its gripe of bud-stipple,

rocking there, parsing this rife morning with pale chits,

snips, staccato bits, and lilting scraps of airsurf--

while here, inside, the caged parakeet’s tumult

of sky-jones and waterpeal roars in the dormer

like the body’s grammar, locked heart singing out, out,

cries wilder for their fractured passage to the open air.

BEHOLD THE HUMAN BEING--BEHOLD A RIGHTEOUS MAN

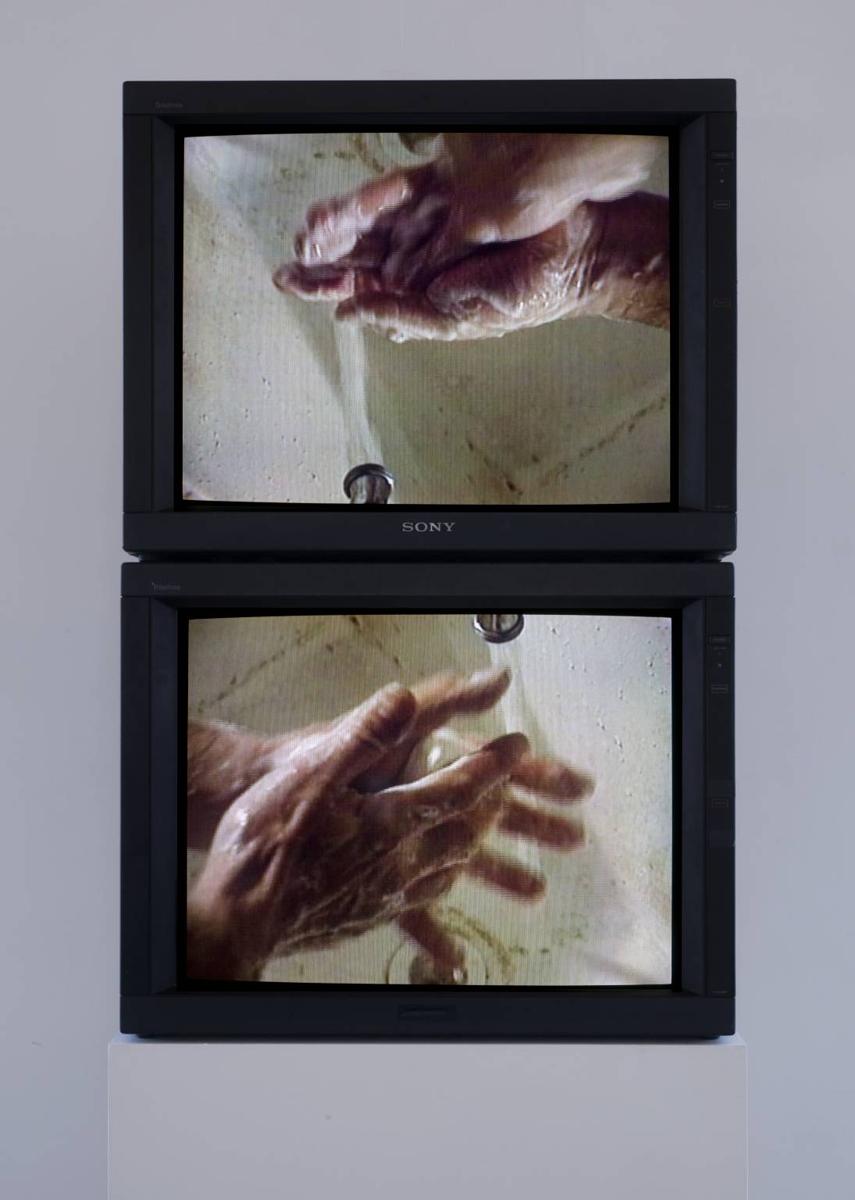

Bruce Nauman’s installation features a video recording of himself washing his hands for 55 minutes. A second monitor placed atop the first plays the recording upside down, producing an unsettling atmosphere of mirrored sounds and images. One recalls Lady Macbeth, trying to purge the imagined blood of her victim, “Come out, damned spot! Out, I command you!” As the videos play, a synergy of allusions slowly begins to reveal a frantic quest for absolution embedded in a simple practice. One of the most obvious allusions is, of course, to Pilate’s infamous act at the end of his meeting with Jesus. Standing before a crowd clamouring for Jesus’s blood, Pilate pours water over his hands and declares himself innocent of what happens next. While Pilate’s literal hand-washing may have only lasted 30 seconds, the reality of his interaction with Jesus mirrors Nauman’s piece: in the moment he met Jesus, Pilate began attempting to wash his hands of Him.

Matthew 26:18 tells us that when the Pharisees first bring Jesus to Pilate, he knows “it was out of envy...” Pilate is no jejune politician; he understands immediately that Jesus is not simply a criminal guilty of breaking the Jewish law, but that He must possess a power that the Pharisees fear. Whatever strange power this man possesses, it is inscrutable to Pilate—it transcends the kind of political or military power that had established and maintained the Roman Empire, and Pilate seems to fear becoming entangled with it. Thus, in a first attempt at “washing his hands” of Jesus, Pilate sends him to be tried by Herod instead (Mark 23:7). When that fails, Pilate attempts to defer to the court of public opinion. But the people choose Barabbas and demanded that Jesus be crucified. Hoping to quell their bloodlust, Pilate hands Jesus off to the Roman centurions, who beat him beyond recognition, only to send him back to Pilate, this time hideously ornamented with a crown of thorns and a purple robe. It is now that the Pharisees reveal to Pilate that Jesus’s crime was that he “claimed to be the son of God” (John 19:7). Meanwhile, Pilate has received his wife’s chilling message: “Have nothing to do with that righteous man, for I have suffered much because of him today in a dream.” Surely, the mutilated body of the man in front of Pilate would confirm that this is no king, much less a god. But John’s gospel tells us that Pilate “consider[s]” these words and becomes “very afraid.”

The further the trial progresses, the less likely it seems to Pilate that Christ is just another zealot or a naïve and deluded rabbi. This leaves him with the most terrifying possibility of all: that Jesus’ testimony is true. Yet, rather than consider and respond to the implications of this truth, Pilate continues, doggedly, to wash his hands. In perhaps his most desperate attempt to evade Christ, Pilate tries to reach consensus with an angry mob, petitioning the crowd on behalf of Jesus as if he, the judge, has no agency in the matter. According to Josephus, Pilate was a brutal ruler who had little regard for the lives or customs of the Jewish people. Yet in this moment, he is overcome with fear. Pilate concludes the trial without a verdict, proceeding to wash his hands before the crowd—a symbol he appropriates from the Mosaic law—signifying that he is “innocent of this man’s blood.” What began as a trial outside the purview of Roman law has spiraled inexorably out of control, drawing Pilate into the eye of human history’s vortex.

This story is traditionally represented as a choice the non-believer encounters: to believe Jesus is the son of God or not. Yet, I find it uncomfortably resonant with my experience as a Christian. Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote, “When Christ calls a man, he bids him to die.” The way of Christ is often horrifying to my reason and flesh. Furthermore, my arguments against His ways are endorsed by the deafening “crowd” shouting the wisdom of the age. Like Pilate, I imagine my logics vindicated—until I suddenly realize I am repeating the all-too-familiar act of washing my hands of him, pretending I do not hear His voice, and putting off responding to His invitation to surrender my truth to His. How often I avow my own innocence and deny the knowledge of this meek man, Jesus. But if I avoid His invitation to die, I abandon the path to life.

Prayer:

Jesus, I surrender to you. I repent for trying to avoid you. You are truth, you are life, you are the wisdom of God. Let your truth expose all fear, doubt, and shame in me. Holy Spirit, lead me in the the way you are calling me; give me ears to hear and eyes to see.

Amen

Christian Gonzalez Ho

Cultural Theorist / Co-founder of Estuaries

For more information about the artwork, music, and poetry selected for this day, we have provided resources under the “About” tab located next to the “Devotional” tab.

About the Artwork:

Raw Material Washing Hands, 1996

Bruce NaumanVideo, 2 monitors, colour and sound

(Monitor 1) - 55 min, 46 sec

(Monitor 2) - 55 min, 56 sec

In the Collection of the Tate and the

National Galleries of Scotland

This stacked two-screen video installation shows the artist washing his hands with a vigor that goes beyond a daily cleaning ritual. The energy of the gesture and the distortive effect of the double screen seem to evoke a sinister prior event and a sense panic or fear. Here Nauman continues his ongoing investigation into human psychology and feelings of discomfort. The sense of anxiety is heightened by the echoing sound of the water draining away for the fifty-five-minute duration of the double footage.

About the Artist:

Bruce Nauman (b. 1941) is an American performance and video artist who has also done sculpture, photography, neon, drawing, and printmaking. He has been one of the most prominent and influential American artists to emerge in the 1960s. The revival of interest in Marcel Duchamp in the 1960s influenced Nauman in various ways, encouraging his love of wordplay and infusing his work with satire. Some of Nauman's earliest work was also shaped by ideas that arose in Minimalism in the late 1960s relating the body to surrounding objects. However, he shunned slick production values of Minimalism and much of Nauman's work reflects the disappearance of the old modernist belief in the ability of the artist to express clearly and powerfully. Ludwig Wittgenstein's ideas helped shape his interest in the complexity of language and despite the impact of Dada, he has continued to view his art less as a playful or creative enterprise than as a serious research endeavor, shaped by his interests in language, ethics and politics.

About the Music:

“Turangalila Symphonie: 9. Turangalila 3” from the album Messiaen: Turangalila Symphony

About the Composer:

Olivier Messiaen (1908–1992) was a French composer, organist, ornithologist, and one of the major composers of the 20th century. His innovative use of colour, his conception of the relationship between time and music, and his transcription and use of birdsong are among the features that make Messiaen's music distinctive. When France fell in 1940, Messiaen was made a prisoner of war, during which time he composed his "Quartet for the End of Time" inspired by Revelation Chapter 10. While most of Messiaen's compositions are religious in inspiration, the Turangalîla Symphony forms the central work in his trilogy of compositions concerned with the themes of romantic love and death; the other pieces are Harawi for piano with soprano and Cinq rechants for unaccompanied choir. It is considered a 20th-century masterpiece and a typical performance runs around 80 minutes in length.

About the Performers:

Yvonne Loriod, Jeanne Loriod, Orchestre de l'Opera Bastille conducted by Myung-Whun Chung

French pianist Yvonne Loriod-Messiaen (1924 - 2010) was the second wife of Olivier Messiaen. She was his pupil when she was at the Paris Conservatoire in 1941 and they got married in 1961. Messiaen quickly saw that Yvonne Loriod was somebody whose technique could interpret his music as he saw it. He dedicated "Vingt Regards sur 'Enfant Jesus,” "Visions de Amen,” "Catalogue d'Oiseaux", "La Fauvette des Jardins", "Petites esquisses d'oiseaux" and most of the piano parts in his orchestral works to her. Yvonne Loriod was also a composer, writing several works including "Grains de Cendre" (1946) for Ondes Martenot, piano and voice; but the only one to be performed in public was probably "Trois Mélopées Africaines" for flute, Ondes Martenot, piano and drum. Yvonne Loriod was also a renowned concertist and soloist.

Jeanne Loriod (1928-2001) was the leading exponent of the Ondes Martenot, an early electronic musical instrument invented in the 1920s by Maurice Martenot who was inspired by the accidental overlaps of tones between military radio oscillators and who wanted to create an instrument with the expressiveness of the cello. Jeanne Loriod was sister to pianist Yvonne Loriod, wife of Olivier Messiaen, whose "Turangalîla Symphony" Jeanne recorded six times. She played with the most famous orchestras and conductors around the world, premiering more than 100 works by André Jolivet, Arthur Honegger, and Jacques Charpentier, to name but a few.

The Orchestre de l'Opéra National de Paris is a French Symphonic Orchestra dating from 1672. Since the opening of the Opéra Bastille in 1989, the orchestra has also been called the Orchestre de l'Opéra Bastille.

Myung-whun Chung (b. 1953) is a South Korean conductor and pianist. A student of Olivier Messiaen, he is particularly known for his interpretations of the French composer's works. Chung was an assistant conductor at the Los Angeles Philharmonic during the music directorship of Carlo Maria Giulini and founder of the Asia Philharmonic Orchestra. He has conducted many prominent European and American orchestras and from 1989 to 1994 served as the Music Director of the Paris Opera. In 1991, the Association of French Theatres and Music Critics named him "Artist of the Year," and in 1992 he received the Legion of Honour for his contribution to the Paris Opera. An exclusive recording artist for Deutsche Grammophon since 1990, many of his numerous recordings have won international prizes and awards. These include Messiaen's Turangalîla-Symphonie.

About the Poet:

Lisa Russ Spaar (b. 1956) received a BA from the University of Virginia in 1978 and an MFA in 1982. She is the author of several poetry collections, including Orexia (2017), Vanitas, Rough (2012), and Glass Town (1999). The Boston Review notes, “Lisa Russ Spaar’s intensely lyrical language—baroque, incantory, provocative—enables her to reinvigorate perennial subject matter: desire, pursuit, and absence; intoxication and ecstasy; the transience of earthly experience; the uncertainties of god and grave; the dialectic between fertility and mortality.” She is also the author of The Hide-and-Seek Muse: Annotations of Contemporary Poetry (2013), a collection of poetry history and criticism, and she was a 2014 finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Citation for Excellence in Reviewing. She has edited multiple poetry anthologies, including Monticello in Mind: Fifty Contemporary Poets on Jefferson (2016). Spaar has received a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Library of Virginia Award for Poetry, and a Rona Jaffe Award, among other honors and awards. She is a professor of English and Creative Writing at the University of Virginia.

About the Devotional Writer:

Christian Gonzalez Ho

Writer, Designer, and Cultural Theorist

Christian Gonzalez Ho is a cultural theorist, writer, and designer. He holds an M.A. in Architecture from Harvard University. Christian's work focuses primarily on the way art and architecture relate to the epistemologies of a culture. Christian and his wife, Christina Gonzalez Ho (HLS ’14), live in Los Angeles. In 2018, they wrote Los Angeles: Mestizo Archipelago (Pinatubo Press), an ethnography of the Los Angeles contemporary art world and its relationship to faith and spirituality. Christian and Christina are also the creators and directors of Estuaries, an experiment in cultivating space for young Christian thinkers to rigorously consider their faith in contemporary society, encounter God, and reimagine the structures and possibilities of their disciplines.