March 18: The Lord is with You

♫ Music:

WEEK SIX - MEDITATING ON THE WORD

March 18 - March 24

The image of a cow chewing its cud slowly and purposefully is used throughout Christian history to emphasize the importance of not just reading the words of God but meditating on them as well. In the words of the Carthusian monk Guigo II, “Reading is the careful study of the Scriptures… Meditation is the busy application of the mind to seek… for knowledge of hidden truth.” Meditation seeks to understand the words of God in all their fullness, as we ask the Holy Spirit to show us not only what we need to see in the text, but also to know what to do in light of the text. As well, meditation creates a desire in us for more; that as we experience the sweetness of the words of God in meditation, we desire more. We find the aroma of Christ (2 Cor. 2:15) so pleasing that we desire more of it. Meditation is to reading what swallowing is to eating – it is the internalization of what we are taking in. Thus, meditation is a necessary corollary to reading.

Day 33 - Sunday, March 18

Title: The Lord is with You

Scripture: Joshua 1:8-9

This book of the law shall not depart from your mouth, but you shall meditate on it day and night, so that you may be careful to do according to all that is written in it; for then you will make your way prosperous, and then you will have success. Have I not commanded you? Be strong and courageous! Do not tremble or be dismayed, for the Lord your God is with you wherever you go.”

Poetry: Supernatural Love

By Gjertrud Schnackenberg

My father at the dictionary-stand

Touches the page to fully understand

The lamplit answer, tilting in his hand

His slowly scanning magnifying lens,

A blurry, glistening circle he suspends

Above the word “Carnation.” Then he bends

So near his eyes are magnified and blurred,

One finger on the miniature word,

As if he touched a single key and heard

A distant, plucked, infinitesimal string,

“The obligation due to everything

That’s smaller than the universe.” I bring

My sewing needle close enough that I

Can watch my father through the needle’s eye,

As through a lens ground for a butterfly

Who peers down flower-hallways toward a room

Shadowed and fathomed as this study’s gloom

Where, as a scholar bends above a tomb

To read what’s buried there, he bends to pore

Over the Latin blossom. I am four,

I spill my pins and needles on the floor

Trying to stitch “Beloved” X by X.

My dangerous, bright needle’s point connects

Myself illiterate to this perfect text

I cannot read. My father puzzles why

It is my habit to identify

Carnations as “Christ’s flowers,” knowing I

Can give no explanation but “Because.”

Word-roots blossom in speechless messages

The way the thread behind my sampler does

Where following each X I awkward move

My needle through the word whose root is love.

He reads, “A pink variety of Clove,

Carnatio, the Latin, meaning flesh.”

As if the bud’s essential oils brush

Christ’s fragrance through the room, the iron-fresh

Odor carnations have floats up to me,

A drifted, secret, bitter ecstasy,

The stems squeak in my scissors, Child, it’s me,

He turns the page to “Clove” and reads aloud:

“The clove, a spice, dried from a flower-bud.”

Then twice, as if he hasn't understood,

He reads, “From French, for clou, meaning a nail.”

He gazes, motionless. “Meaning a nail.”

The incarnation blossoms, flesh and nail,

I twist my threads like stems into a knot

And smooth “Beloved,” but my needle caught

Within the threads, Thy blood so dearly bought,

The needle strikes my finger to the bone.

I lift my hand, it is myself I’ve sewn,

The flesh laid bare, the threads of blood my own,

I lift my hand in startled agony

And call upon his name, “Daddy daddy”—

My father’s hand touches the injury

As lightly as he touched the page before,

Where incarnation bloomed from roots that bore

The flowers I called Christ’s when I was four.

THE LORD IS WITH YOU

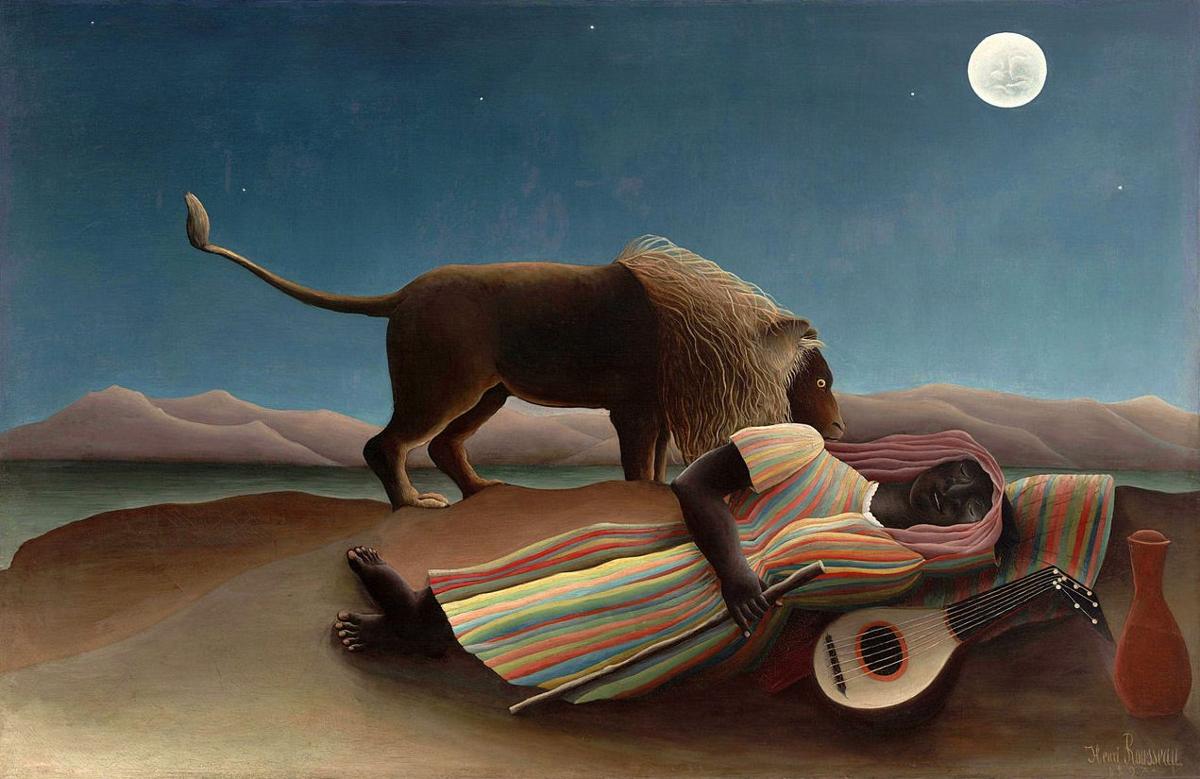

Travel can increase our adventures and opportunities, and it can also increase our vulnerability, especially as we get farther from our base and more alone. Rousseau’s Sleeping Gypsy is dangerously vulnerable – a woman, an outsider, alone, without shelter, her means of livelihood and sustenance all exposed to the elements and the whims of each passersby, both human and animal. Rousseau wrote that the lion picks up her scent and does not devour her; however, interestingly we do not see the lion’s mouth in the painting, and so do not know the end of her story.

The Israelites had been traveling for over 40 years at the time that their narrative continues from the Book of Deuteronomy to the Book of Joshua. During those years, although vulnerable to thirst, hunger, and death, the Israelites’ primary vulnerability was to distrustfulness of God’s words as given to them through Moses. They struggled to trust what they could not experience in the moment, be it food, water or the Promised Land.

As part of his farewell in Deuteronomy, Moses told collective Israel to be strong and courageous and then turned to Joshua individually and told him to be strong and courageous. These exhortations from Moses at the end of Deuteronomy have a military feel, that of a commanding officer addressing his troops. As Joshua opens, when God tells Joshua to be strong and courageous as the new leader, there is a new focus of the exhortation – to be strong and courageous in obeying the Law of Moses.

To obey the Law of Moses, we need to know the Law of Moses. We learn some by repetition, such as the ancient practice of reading aloud to oneself as an aid to memorization referenced in today’s passage; we learn more by finding meaning in the words we are rehearsing. Part of the wonder and beauty of God’s word is that not only are we commanded to be strong and courageous in obeying it, our very meditation on God’s word makes us strong and courageous.

Meditation on God’s word strengthens and encourages us as it embeds in our spirits “X by X” that we are not alone, our daily experience is not all that there is, and we are loved. In contrast to how The Sleeping Gypsy is portrayed, we are never alone. God is both omnipresent and intimate through His indwelling Holy Spirit. Regardless if the lion devourers Sleeping Gypsy on that night or the next, it is not the end of her story. All of our stories extend beyond our lives on earth, either to be fully in God’s presence or fully outside of it. And we are loved. Words on a page can tell us that we are loved; nails through Christ’s flesh show us that we, and all our fellow travelers, are loved. Vulnerable to the ease of only trusting what we experience each day, such truths from God’s word sustain us as we travel to our journey’s end.

Prayer:

O God, our heavenly Father, whose glory fills the whole

creation, and whose presence we find wherever we go:

Preserve those who travel;

surround them with your loving care; protect them from every danger;

and bring them in safety to their journey's end; through

Jesus Christ our Lord.

Amen.

From Book of Common Prayer

Nancy Crawford

Associate Professor of Psychology

Rosemead School of Psychology

Biola University

The Sleeping Gypsy

Henri Rousseau

1897

Oil on canvas

129.54 × 200.66 cm

Museum of Modern Art, New York

The Sleeping Gypsy features a moonlit scene in a desert where a female gypsy sleeps with a mandolin and jug by her side, untroubled and - amazingly - unharmed by a curious lion. The presence of the lion that should evoke danger rather gives the image a strong sense of peace and tranquility. The gypsy is dressed in Eastern garb, while the painting recalls the stories from Arabian Nights, which had been translated into several unabridged versions in the mid-1880s. For its eerie, meditative beauty and image of humankind's harmony with the animal kingdom, The Sleeping Gypsy has attained iconic status as various artists have parodied it.

About the Artist:

Henri Rousseau (1844-1910) was a French Post-Impressionist painter in the Naïve or Primitive style. Formerly a toll and tax collector, Rousseau started painting seriously in his early forties and at age 49, he retired from his day job to work full-time on his art. Although an admirer of artists such as the classical William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Jean-Leon Gerome, the self-taught Rousseau became the archetypal naïve artist. His amateurish technique and unusual compositions provoked the derision of contemporary critics, while earning the respect and admiration of modern artists like Pablo Picasso and Wassily Kandinsky. They saw in Rousseau's work a sincerity and directness to which they aspired in their own work. The Surrealists whose art valued the surprising juxtapositions and dream-like moods characteristic of his work also celebrated his work, imbued with a sense of mystery and eccentricity.

About the Music:

“Burying Song” from the album Rabbit Songs

About the Composer:

Daniel Messé is the founder/principal songwriter of the band Hem, which began in 2001, and has since gone on to worldwide acclaim over the course of six studio albums. In 2009, The Public Theater tapped Hem to score Twelfth Night for Shakespeare in the Park for which they were nominated for a Drama Desk Award. Along with collaborator Mindi Dickstein, Dan has written four other shows for Theatreworks USA, received a Jonathan Larson Grant from the American Theatre Wing. Messé has recently composed the musical score for the Broadway adaptation of the film Amélie.

About the Performers:

Hem is a musical group from Brooklyn, New York. Band members include Sally Ellyson (vocals), Dan Messé (piano, accordion, glockenspiel), Gary Maurer (guitar, mandolin), Steve Curtis (guitar, mandolin, banjo, back-up vocals), George Rush (bass guitar), Mark Brotter (drums), Bob Hoffnar (pedal steel guitar), and Heather Zimmerman (violin). The group sometimes expands to include other musicians and orchestral accompaniments. Stylistically, Hem’s songs bridge 19th-century American parlor music, Appalachian folk music, gospel music, traditional American ballads, the European art song, early jazz, and even contemporary classical music.

About the Poet:

Gjertrud Schnackenberg (b.1953) is an American poet who began writing poetry as a student at Mount Holyoke College where she earned the reputation as a poetic prodigy by twice winning the Glascock Award for Poetry. Her first two books of poetry, Portraits and Elegies and The Lamplit Answer, established her as one of the strongest poets of the New Formalists. In reviewing The Lamplit Answer, critic Rosetta Cohen noted Schnackenberg’s “talent for creating small, intricate worlds [which] seems to place Schnakenberg within a tradition that has less to do with a particular poetic mode than it does with the nineteenth-century novel.” Schnackenberg’s third book, A Gilded Lapse of Time revealed the influence of Eliot, Yeats, Auden, and Lowell and demonstrated a mastery of dense metered lines on subjects ranging from classical philosophy to Christian theology and Russian poetry.

About the Devotional Writer:

Nancy Crawford, Psy.D., serves as the Director of Clinical Training at Rosemead, and as a former missionary, is involved whenever possible in providing care to missionaries and their families. She is an avid morning walker always on the lookout for a bird species she has not seen before.