March 19: The Remorse of Judas

♫ Music:

Wednesday, March 19—Day 15

David & Christ: The Betrayal of Friends

“Even my close friend in whom I trusted, who ate my bread, has lifted up his heel against me.”

“I am not speaking of all of you; I know whom I have chosen. But the Scripture will be fulfilled: ‘He who ate my bread has lifted his heel against me.’ I am telling you this now, before it takes place, so that when it does take place you may believe that I am he. Truly, truly, I say to you, whoever receives the one I send receives me, and whoever receives me receives the one who sent me.” After saying these things, Jesus was greatly troubled in his spirit, and testified, “Truly, truly, I say to you, one of you will betray me.”

When evening came, Jesus arrived with the Twelve. While they were reclining at the table eating, he said, “Truly I tell you, one of you will betray me—one who is eating with me.” They were distressed, and one by one they said to him, “Surely you don’t mean me?” “It is one of the Twelve,” he replied, “one who dips bread into the bowl with me. The Son of Man will go just as it is written about him. But woe to that man who betrays the Son of Man! It would be better for him if he had not been born.”

Psalm 41:9, John 13:18-21, Mark 14: 17-22

The Remorse of Judas

In 2 Samuel 15–17 we read the account of a vicious insurrection against King David led by his son, Absalom. While standing outside Jerusalem on the Mount of Olives (2 Sam 15:30–31), David learns that his most trusted advisor, Ahithophel—a man so wise that David considered his council “like that of one who inquires of God” (16:23)—has also joined the conspiracy against him. This is extremely painful news to David, as attested to in Psalm 41, where it seems that Ahithophel is precisely the man in view as David complains that even his dear friend “has lifted up his heel against me.” And as we turn to the gospel of John, we find Jesus borrowing this particular line from David to articulate the profound sense of betrayal he will experience from within the circle of his closest disciples (John 13:18).

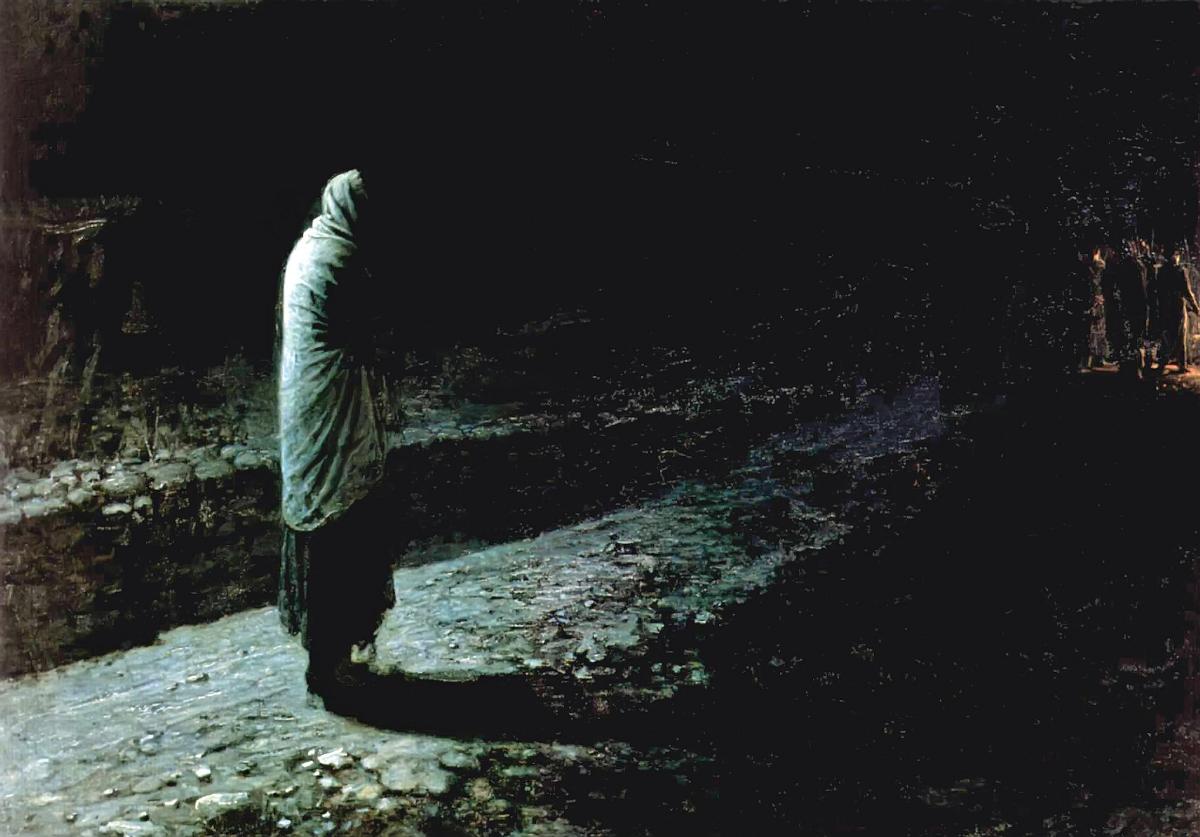

Whereas most artistic depictions of the arrest of Christ focus on the moment that Judas betrays Jesus with a profoundly disturbing kiss, nineteenth-century Russian artist Nikolai Ge invites us to linger on the scene and to imaginatively construct Judas’ experience of the minutes that follow. Judas stands immobile in the roadway watching the hot torchlight of the zealous crowd move away from him into the distance. Only minutes prior Judas was at the center of that loud flickering circle, but now he finds himself alone and remarkably cold—and the whole world looks different. The heat of the crowd recedes out of the right side of the composition, and Judas clutches his thin cloak tightly around his body as an icy light and a thick blackness overtake him from behind. Indeed, this is the hour “when darkness reigns” (Luke 22:53).

The road ahead of Judas leads back to Jerusalem. The walls of the unfaithful city of God lie somewhere ahead in the black distance, and the crowd ushers its new prisoner toward the city to face an illegal trial in the house of the high priest (Mark 14:53–65). In the opposite direction, extending behind Judas, the road presumably leads into the desert—perhaps into the same wilderness into which Jesus was led by the Spirit to confront the temptations of the Accuser. Here on a road that cuts through the Mount of Olives, at a point somewhere between the city and the desert, we see Judas overthrown and undone by that same tempter. This suddenly appears as a profoundly barren place, lifeless and difficult—a place groaning with curses, a place of thorns and thistles (Gen 3:17–18). Judas stands alone in the roadway and clutches himself as though he were trying to hold onto himself. Indeed the darkness seems to be consuming him as his face and his heart become visually absorbed into the blackness. He is becoming a void, a something frightfully vacuous. All of his plotting came to completion only moments prior, and whatever satisfaction or profit he may have anticipated has given way to a gaping shame, a state-of-being so “seized with remorse” that no repentance or reconciliation will be found (Matt. 27:3–5). He just committed the profoundest betrayal in history and is becoming the most horrifying kind of barrenness: “It would have been better for that one not to have been born” (Matt 27:24; Mark 14:21).

Prayer

Lord, have mercy.

Christ, have mercy.

Make wide the way of repentance in us,

and graciously close the mouth of the accuser.

Deliver us from evil, and lead us not into temptation.

Deliver us from remorse and from whatever is remorseful in us.

Deliver us from all that darkens and dehumanizes us.

For yours is the fullness and flourishing of life, forever and ever.

Amen.

Jonathan Anderson, Associate Professor of Art

Conscience, Judas

Nikolai Ge

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Oil on canvas

About the Artist and Art

Nikolai Ge (1831-1894) was a Russian realist painter famous for his works on historical and religious motifs. When his parents died while he was still a child, Nikolai was raised by his serf nurse. He graduated from the First Kiev Gymnasium and studied at the physics-mathematics department of Kiev University and Saint Petersburg University. In 1850 he gave up his career in science and entered the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg. He studied in academy under the historical painter Pyotr Basin until he graduated in 1857. At the time, his religious paintings were condemned by conservatives as being blasphemous, as they often depicted a fanciful, non-traditional interpretation of New Testament events. In Conscience, Judas, Nikolai paints Judas, huddled under his cloak, watching as the soldiers lead Jesus away to his trial.

About the Music

J. S. Bach, St. Matthew Passion, BWV 244, no. 27 Lyrics

Thus my Jesus is now captured.

Leave Him, stop, don't bind Him!

Moon and light

for sorrow have set,

since my Jesus is captured.

They take Him away, He is bound.

Are lightning and thunder

extinguished in the clouds?

Open the fiery abyss, o Hell,

crush, destroy, devour, smash

with sudden rage

the false betrayer, the murderous blood!

About the Composer

The St. Matthew Passion is a sacred oratorio from the Passions written by Johann Sebastian Bach in 1727 for solo voices, double choir and double orchestra. It sets chapters 26 and 27 of the Gospel of Matthew to music, with interspersed chorales and arias. It is widely regarded as one of the masterpieces of classical sacred music. The original Latin title Passio Domini Nostri J.C. Secundum Evangelistam Matthaeum translates to "The Passion of our Lord J[esus] C[hrist] according to the Evangelist Matthew."