December 20: Submission and Fullness

♫ Music:

Day 19 - Thursday, December 20

Christ’s Ancestors: From the House of David

Scripture: Luke 2:1-5

In those days a decree went out from Caesar Augustus that all the world should be registered. This was the first registration when Quirinius was governor of Syria. And all went to be registered, each to his own town. And Joseph also went up from Galilee, from the town of Nazareth, to Judea, to the city of David, which is called Bethlehem, because he was of the house and lineage of David, to be registered with Mary, his betrothed, who was with child.

Poetry:

Descending Theology: The Nativity

by Mary Karr

She bore no more than other women bore,

but in her belly’s globe that desert night the earth’s

full burden swayed.

Maybe she held it in her clasped hands as expecting women often do

or monks in prayer. Maybe at the womb’s first clutch

she briefly felt that star shine

as a blade point, but uttered no curses.

Then in the stable she writhed and heard

beasts stomp in their stalls,

their tails sweeping side to side

and between contractions, her skin flinched

with the thousand animal itches that plague

a standing beast’s sleep.

But in the muted womb-world with its glutinous liquid,

the child knew nothing

of its own fire. (No one ever does, though our names

are said to be writ down before

we come to be.) He came out a sticky grub, flailing

the load of his own limbs

and was bound in cloth, his cheek brushed

with fingertip touch

so his lolling head lurched, and the sloppy mouth

found that first fullness—her milk

spilled along his throat, while his pure being

flooded her. (Each

feeds the other.) Then he was left

in the grain bin. Some animal muzzle

against his swaddling perhaps breathed him warm

till sleep came pouring that first draught

of death, the one he’d wake from

(as we all do) screaming.

SUBMISSION AND FULLNESS

Paul writes in Galatians, “…when the fullness of time had come, God sent forth his Son.” “Fullness of time” has such a lovely, poetic sound. One imagines Paul looking back over salvation history with such rapture that he momentarily stops writing. Such rapture animates Luke’s juxtaposition of Mary’s Magnificat and Zechariah’s song. But Luke almost immediately undercuts these poetic salvos with a shift that displays God’s humor as well as providence. Who but the Lord would plan for the “fullness of time” to coincide with something so thoroughly bureaucratic, inconvenient, daunting, and mind-numbing as a census?

A census has no interest in the individual person save in their most reduced, statistical existence. One gets the sense of this compression in the way Luke’s account pivots from the theater of international politics to the personal dimensions of the holy family where Jesus is present but not yet born or named. The angelic visitations fill Mary and Joseph with joy as they consider the mysterious ways of God, but their minds may have also turned with less reverence to the ways of Caesar, whose imperial caprice God had chosen to employ. I imagine they felt variously vulnerable, exhausted, and bewildered—forced to submit to forces beyond their control or perception, and whose consequences remained uncertain. That God chooses Mary and Joseph endows them with unimaginable honor, but it does not deliver them from the hardships of human experience. The Incarnation does nothing to repeal the pain of pregnancy or reduce the ninety miles between Nazareth and Bethlehem.

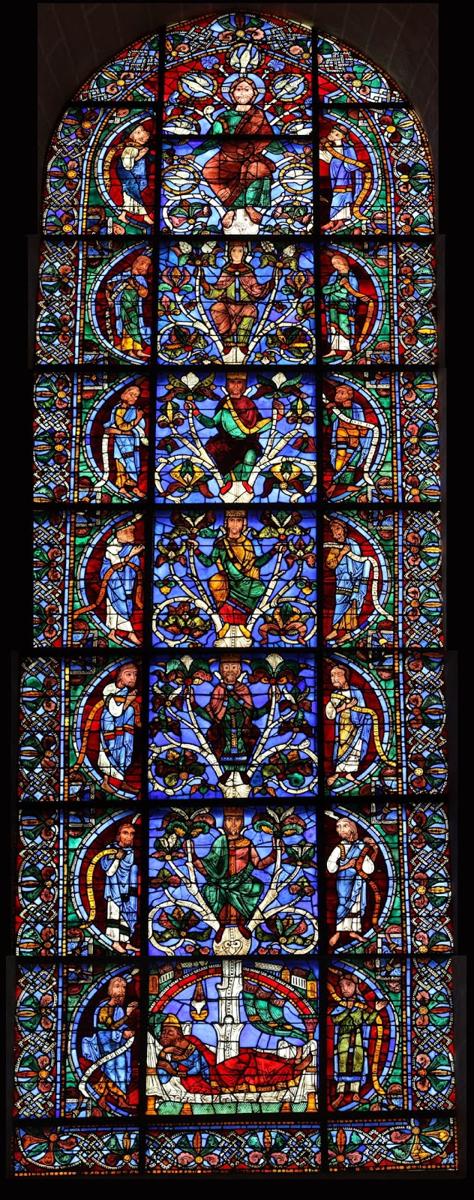

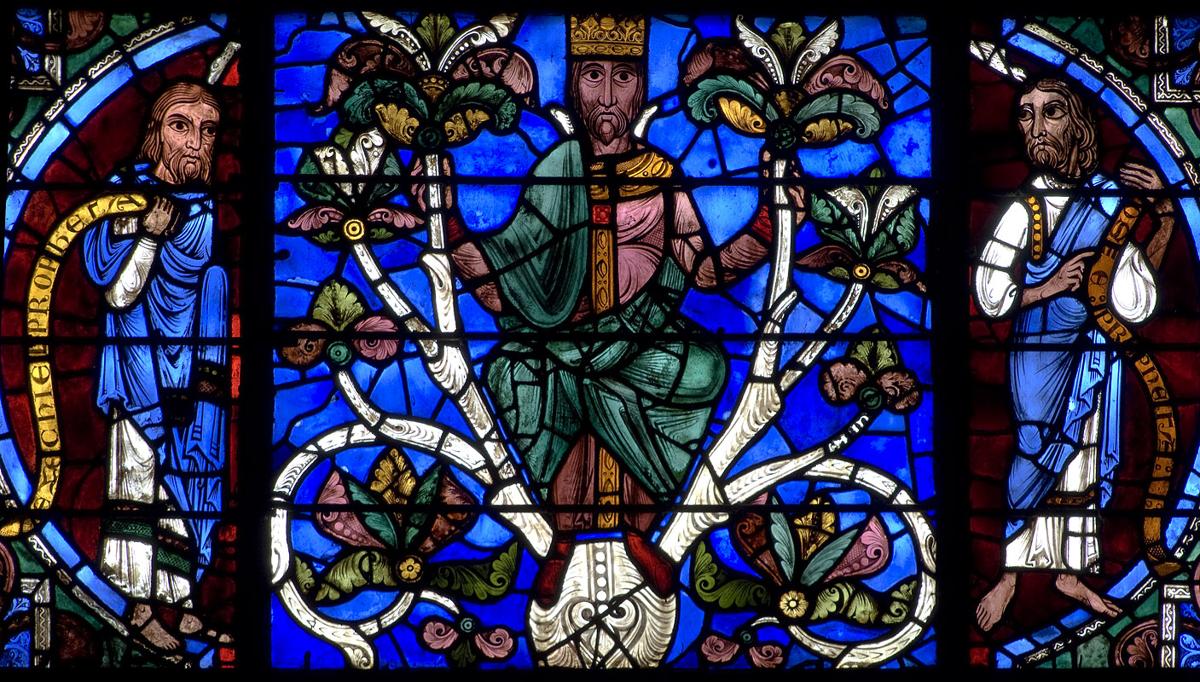

The stained-glass window, Tree of Jesse, likewise reminds us that God’s providence invites our submission to forces and narratives whirling beyond our agency. Sometimes we barely know more than the role assigned to us for a particular season. Jesse lies supine at the bottom of window while a tree trunk emerges from his midsection. The image oddly but forcefully evokes pregnancy. The tree proceeds up the window, yielding further generations until Christ himself gloriously crowns the window and Jesse’s lineage. But Jesse turns away and his eyes remain closed. He cannot see the beauty or order of God’s plan. He cannot even see to his own son, David, let alone to the figure of Christ. The window invites us to suspect that he rather feels what he cannot see. Tree of Jesse depicts Jesse in fairly traditional ways. Between the 11th and 17th centuries, many artists depicted the genealogy of Christ in this way. Jesse often lies upon his back while from his belly grows a slender root that flowers through further generations of figures until Christ emerges. In many of these Jesse’s posture is that of repose combined, effectively, with blindness. His eyes are closed, shielded, or else turned away.

Mary Karr’s poem bristles with similar paradox as she presents the cosmic miracle of the Incarnation which, nonetheless, affords Mary no immediate material comfort. The opening lines juxtapose these two sensibilities: “She bore no more than other women bore / but in her belly’s globe that desert night the earth’s/ full burden swayed.” The first line’s matter-of-fact tone, the compression of Mary to a “she” among all of history’s mothers recalls the way that Luke’s account of the census renders Joseph, Mary, and Jesus almost anonymous. Further juxtapositions of this sort occur. Karr connects images of celestial beauty and portent to those of intimate threat and pain in ways that might remind us of Jesse’s ambivalent posture toward his glorified heirs: “Maybe at the womb’s first clutch /she briefly felt that star shine / as a blade point, but uttered no curses.” Mary instead encounters joy and peace through her obedience and motherhood. But Karr aims at realism more than happy endings. The poem concludes with the disconcerting relationship between sleep and death. The final act and image of screaming (an experience that unites us with Christ as a child) emerges upon the recognition of our vulnerability and need.

The Incarnation does not deliver us from these conditions most of the time. Rather, we find that Christ becomes more and more present to us in the midst of them. As we submit to his path we each find greater joy in obedience and transform ever more into his likeness.

Prayer:

O God: grant us, in all our doubts and uncertainties, the grace to ask what you would have us do, that your Spirit of wisdom may guide us through all seasons and occasions—that in your light we may see light, and in your straight path may not stumble. Give us joy in submitting to your direction and patience as we learn to trust in the perfection of your plans for us, through Jesus Christ our Lord.

Amen.

Dr. Phillip Aijian

Adjunct Professor

Torrey Honors Institute

About the Artwork:

Tree of Jesse, 1140-50 (view of entire window)

Separate detail panels of the window:

Panels 01-03 - Nahum / Jesse with the 'stem' growing from his loins / Joel

Panels 04-06 - Ezekiel / David / Hosea

Panels 07-09 - Isaiah / Solomon / Micah

Panels 10-12 - Moses / Generic King of Israel / Balaam

Panels 13-15 - Samuel / Generic King of Israel / Amos

Panels 16-18 - Zachariah / The Virgin Mary / Daniel

Panels 19-22 - Habakkuk / Christ with the Seven Gifts of the Spirit / Zephaniah

Stained-glass lancet window

West facade

Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, France

The Tree of Jesse is a representation of the genealogy of Christ based on the prophecy of Isaiah:11:1, “And there shall come forth a rod out of the stem of Jesse and a branch shall grow out of his roots.” First appearing in the eleventh century, it is a popular subject of Medieval art. The stained-glass window at Chartres Cathedral pictures a tree that springs from the loins of a sleeping Jesse. From Jesse proceeds King David, Solomon, two more unidentified kings, Mary, mother of Jesus, and at the top, Christ, twice the size of the others surrounded by the seven doves representing the gifts of the Holy Spirit. Flanking each of these figures are prophets holding scrolls who foretold the coming of Christ. Typical of Medieval stained-glass, the scenes read bottom to top, directing our sight heavenward to remind us of God’s providence.

About the Artist:

Unknown

About the Music:

“Es ist ein Ros entsprungen” from the album A String Quartet Christmas

Lyrics

Lo, how a Rose e’er blooming

From tender stem hath sprung!

Of Jesse’s lineage coming,

As men of old have sung.

It came, a flow’ret bright,

Amid the cold of winter,

When half spent was the night.

Isaiah ’twas foretold it,

The Rose I have in mind;

With Mary we behold it,

The virgin mother kind.

To show God’s love aright,

She bore to men a Savior,

When half spent was the night.

This Flow’r, whose fragrance tender

With sweetness fills the air,

Dispels with glorious splendor

The darkness everywhere.

True man, yet very God,

From sin and death He saves us,

And lightens every load.

About the Composer:

Michael Praetorius (c. 1571–1621) was a German composer, organist, and music theorist. He was one of the most versatile composers of his age and was particularly significant in the development of Protestant hymns. Praetorius was a prolific composer; his compositions show the influence of Italian composers and of his younger contemporary Heinrich Schütz. His works include the nine-volume collection of more than twelve hundred chorale and song arrangements.

About the Performers:

Alexander Romanul, Arturo Delmoni (Arranger), Katherine Murdock, Nathaniel Rosen

Violinist Alexander Romanul (b. 1961) was born into a distinguished musical family of historic Romanian lineage. After making his debut at age 13 with the New England Conservatory Orchestra, he was invited by conductor Arthur Fiedler to play as a soloist with the Boston Pops. He has also soloed with the Boston Symphony Orchestra in Symphony Hall as winner of the Youth Concerts Concerto Competition and has performed as soloist with the National Symphony of Ecuador, where critics acclaimed him “a poet of the violin.” Subsequently Romanul was awarded fifth prize in the Wieniawski International Violin Competition in Poland and has performed widely as soloist and chamber musician in Europe and the Americas.

Arturo Delmoni (Arranger), the Concertmaster of the New York City Ballet, is one of the most celebrated artists of his generation. His remarkably distinctive playing embodies the romantic warmth that was the special province of the great virtuosi of the golden age of violin playing. Yo-Yo Ma describes Delmoni as “an enormously gifted musician and an impeccable violinist. His playing style is unique, and his gorgeous sound is reminiscent of that of great violinists from a bygone era.” Delmoni’s stylish, elegant interpretations of classical masterpieces have earned him critical acclaim in the United States and abroad. He has appeared as a recitalist throughout the US and Europe, as well as Japan and Hong Kong.

Katherine Murdock is a violinist who has performed as soloist and chamber musician in the musical capitals of the U.S., Europe, Canada, New Zealand, and South America. A recipient of two Canada Council Arts Awards, she received her musical training at Oberlin College and Boston University, and pursued graduate studies at Yale School of Music. From 1988 to 1994, Ms. Murdock was a member of the Mendelssohn String Quartet. As a member of the Mendelssohn Quartet, she served as Artist-in-Residence at Harvard University and the University of Delaware. Murdock has previously been on the faculties of Wellesley College, the Boston Conservatory, the Hartt School of Music, and Stony Brook University. Ms. Murdock’s extensive orchestral experience includes performances, tours, and recordings with the Boston Symphony, the National Symphony, the New York Philharmonic, and the Boston Musica Viva, with whom she recorded and performed internationally.

Nathaniel Rosen (b. 1948) is an American cellist, the gold medalist of the 1978 International Tchaikovsky Competition, and former faculty member at the USC Thornton School of Music and the Manhattan School of Music. Rosen became only the second-ever American gold prize winner of the International Tchaikovsky Competition after pianist Van Cliburn and is still the only American cellist to take first prize at the competition. He has soloed with the New York Philharmonic, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Czech Philharmonic, London Symphony Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra, Dresden Philharmonic Orchestra, and Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra. Since 2011 he lives in Japan with his wife and daughters. His historic cello was crafted in 1738 by Italian master luthier Domenico Montagnana, the "Mighty Venetian."

About the Poet:

Mary Karr (b. 1955) is an American poet, essayist, and memoirist from Texas. She rose to fame in 1995 with the publication of her bestselling memoir The Liars' Club. She is the Jesse Truesdell Peck Professor of English Literature at Syracuse University in Lima, New York. Her memoir The Liars' Club which delves vividly into her deeply troubled childhood was followed by two additional memoirs, Cherry and Lit: A Memoir, which details her "..journey from blackbelt sinner and lifelong agnostic to unlikely Catholic." Karr won the 1989 Whiting Award for her poetry, was a Guggenheim Fellow in poetry in 2005, and has won Pushcart Prizes for both her poetry and essays. Her poems have appeared in major literary magazines such as Poetry, The New Yorker, and The Atlantic Monthly.

About the Devotional Writer:

Phillip Aijian holds a PhD in Renaissance drama and theology from UC Irvine. He teaches literature and religious studies and has published in journals like ZYZZYVA, Heron Tree, Poor Yorick, and Zocalo Public Square.